An Ethic for All Realms

by Isabel Beavers

Still from ‘The Abyss’, 2023

I sat on an old wooden picnic table, framed by the hanging boughs of an oak tree, the glistening blue lake hazy in the heat of summer. Birds sang many songs, harmonized by the chirping of grasshoppers, crickets, buzzing flies, the distant groan of lawnmowers and boats, alongside echoes of their riders’ laughter – a summertime symphony. I sat and watched the sunlight dim, a flush of pink light along the horizon warning of the coming sunset.

View of Lake Okoboji

This came to be my favorite time of day on Lake Okoboji, as it was in many other parts of the world. Dusk feels like the moments we seize before the sure darkness, the last bits of laughter, the last swim in the lake, a full belly, before day turns into night. I spent most nights in the studio. I wound my way to the Bodine Lab after dinner, through a dense grove of trees and poison ivy via a wooden walkway. Sometimes I would pause during sunset (around 8 or 9 pm this time of year) to walk the bike path by the road. From here you look out towards the vast prairie, the lake hidden by trees and houses. The prairie is fairly flat, with rolling undulating depressions and rises, punctuated by water towers that reach into the sky. It’s green, so green.

Sunset over the Iowa prairie from the bike path.

During my time at the lab I was most surprised at the enthusiasm for the place by the people who call Iowa home.. Not because it doesn’t deserve this endearment, it absolutely does, but because it’s rare to find folx who display this contentment in a place like Los Angeles where I currently live. While beautiful with its arid climate, coastal ecology, and proximity to the Pacific Ocean, Angelenos find myriad frustrations with the place. It’s too hot. It’s too polluted. The seasons don’t change enough. It takes too long to get to the beach. Despite my relative newness to LA, I have found myself swayed by the permeating disaffection with the Place of LA. Maybe the lack of frigid temperatures is suffocating. Maybe the sherbert sunsets do get boring. Maybe 300+ days of sunshine is depressing. Isn’t general dissatisfaction the norm?

I am reminded during my conversations with others at the Lab about Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic, an essay that was seminal to my undergraduate studies in Natural Resource Management at the University of Vermont. We studied the concept of the land ethic, what it means to have a relationship to land, and contemplated what our own land ethic is and could be. Since this time (ca. 2007-2011), new language has emerged with which we talk about human-environment relationships. We have since enjoyed the splendor of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s writings on reciprocity, thought deeply about care, elaborated on our understandings of animal, vegetal and mineral intelligences. We have started thinking about the more-than-human, about the thoughts and feelings of octopus. We might even consider how we, humans, are sensed and understood by the animate creatures around us.

While many feminist, indigenous and queer thinkers have enriched my mind and worldview, the influence of earlier writings on natural history by Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson and EO Wilson on my personal environmental ethic cannot be understated. These writers helped give voice to my deeply intuitive feelings about our home planet. They taught me that thinking seriously about where and how we live is a worthwhile endeavor. That pushing our concerns beyond the confines of the human condition not only is beneficial to other species but also to our own. It was in the Green Mountains of Vermont that I developed my own land ethic. It is in the waters of the Pacific Ocean that it shapeshifts and calcifies.

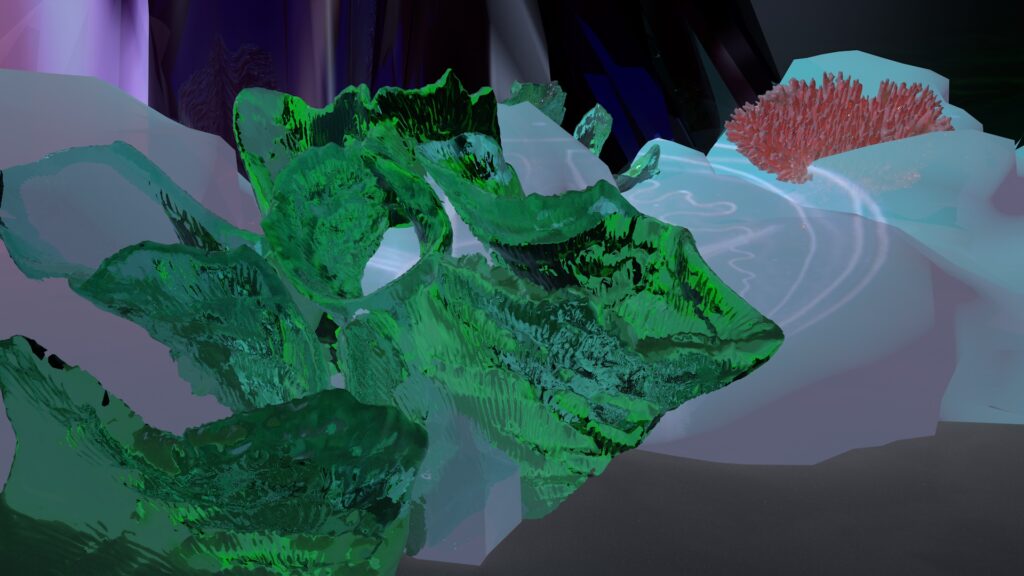

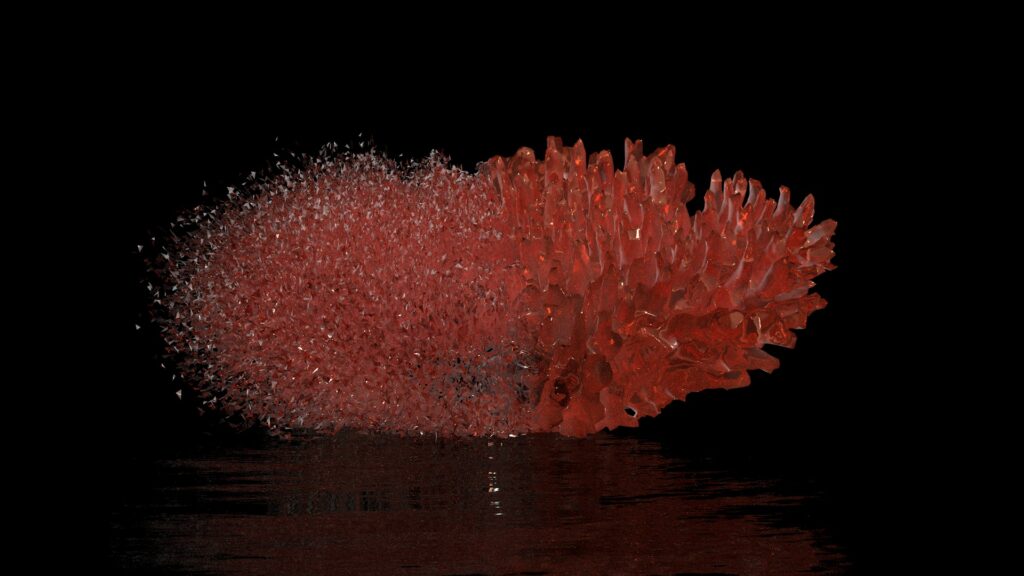

Still from To our fast eyes, they seem still, 2023

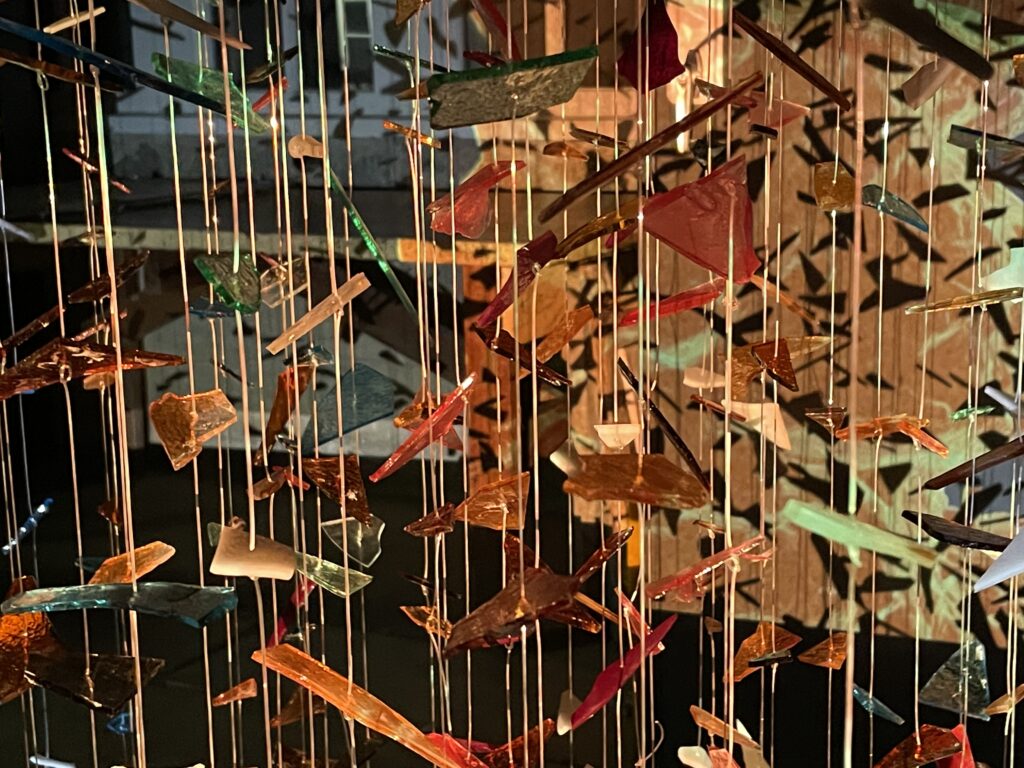

James Bridle, an artist and writer, shared a quote by John Muir in his recent book Ways of Being: ‘Reflecting on the abundance of complex life he encountered while writing his book My First Summer in the Sierra, [Muir] wrote simply: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to anything else in the universe.” While an artist-in-residence at Lakeside Lab I worked on a large-scale sculpture, made of hundreds of pieces of shattered glass. This work, titled what is 500 million years to a shark tooth?, ruminates on a crisis of our oceans: the growing industry of deep sea mining for polymetallic nodules, sulfides, and other extractable resources. In haste we are opening mining permits for the Clarion Clipperton Zone, an area of the seabed in the Pacific Ocean that stretches from Hawaii east towards coastal Mexico. It is home to an enormous field of polymetallic nodules, potato shaped balls composed of metals like cobalt, copper, and manganese. The nodules began as a shark tooth, or piece of fallen coral. Over 500 million years physical processes have turned the organic matter into dense accumulations of precious metals that are used in electric vehicle batteries, electronics like computers, smart phones, and more. These metals also exist on land and we have violently mined them for centuries. There is a vast resource available to us 6000m under the ocean, but at what cost?

In process sculpture What is 500 million years to a shark tooth?

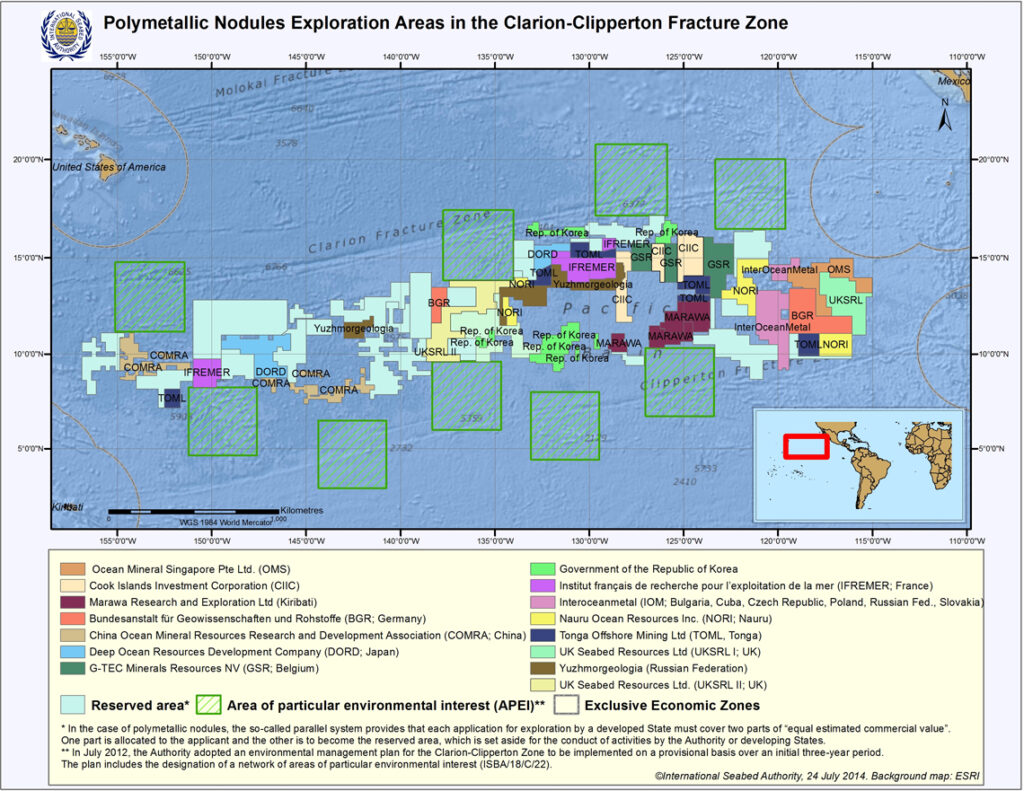

The Clarion Clipperton Zone is in international waters. A transnational organization, the International Seabed Authority, has been created to assist in the management of this area. It is a fledgling organization with offices in Jamaica, tasked with managing the permitting and protection of international seabeds. While there are efforts being made to curb extraction, there is an extreme urgency driven by corporate stakeholders to mine for polymetallic nodules. Deep sea ecologists, like Dr. Diva Amon, Dr. Victoria Orphan, Moronke Harris, and many others (these are the ones with whom I have been in conversation) warn against a hurried approach to mining. The reality is that these deep sea environments are little studied. Only recently have humans had technology that allows us entry to these places that are often more than 6000m underwater. The organisms that live there are largely undiscovered – an estimated 60-80% of the organisms that call this environment home have not been identified. The relative lack of understanding of this ecosystem means we cannot possibly predict the detriment mining-based activities will have on the seabed, and the creatures that inhabit it.

Map showing different country’s mining claim in Clarion-Clipperton Zone, map via International Seabed Authority.

Every night the largest migration on earth by mass happens in the ocean. Cephalopods, ctenophores and millions of other juvenile marine species migrate from the depths of the ocean to the surface of the water under the cover of darkness. Called a diel (or daily) vertical migration, the movement of these organisms is an engine that powers carbon sequestration capacity of the oceans, as well as contributes to thriving food webs, feeding habitats, and more. Undeniably the deep ocean seabed matters – in ways we have not yet come to understand, and also in ways we understand well. The process of mining involves dredging the ocean floor. Imagine a giant rake turning up nodules that are then sucked up through a vertical pipe to the surface of the water where a boat is waiting to receive its bounty. This raking dislodges soil from the bottom of the ocean, creating plumes of turbid water, suffocating ctenophores and other delicate organisms that for millennia have lived in the calm, cold, clear waters of the deep. The disturbance wreaks havoc on the ecosystem.

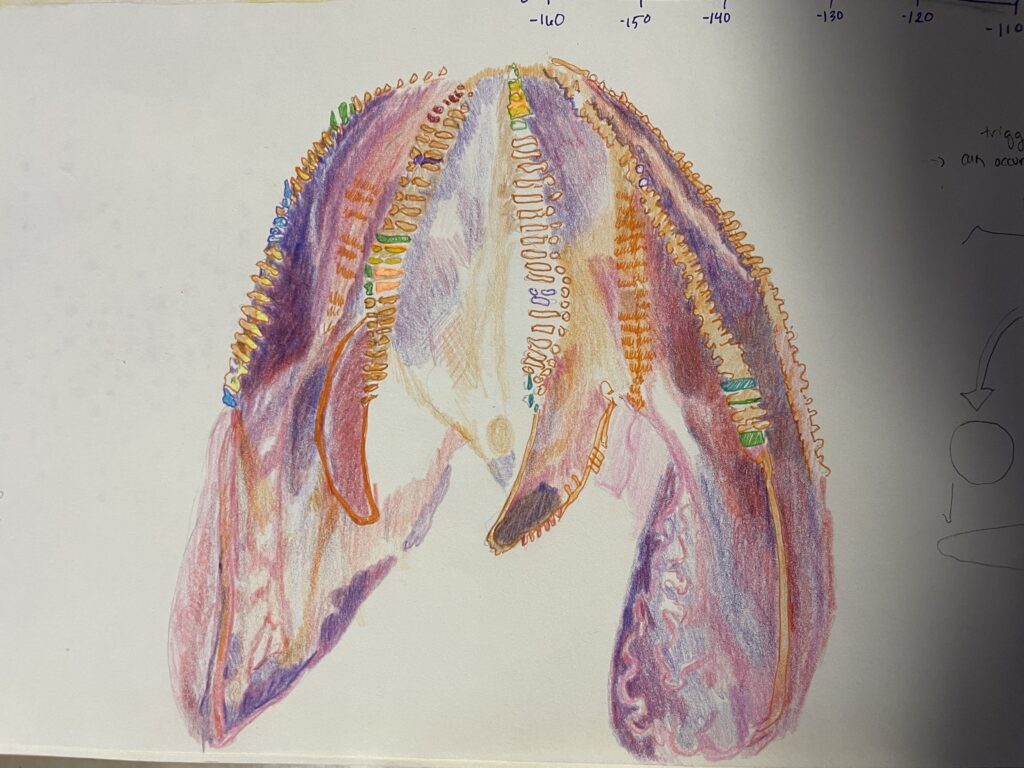

Drawing of blood belly comb jelly, a ctenophore.

I find it ironic how the slowness of the deep sea is threatened by the quickness of technological progress. When I think about the concept of deep time, there is no place on earth that it feels more relevant than the deep ocean. The creatures that live here, like species of ctenophores, evolved earlier in the history of evolution than any other animal. They were the first to have cells that organized into nervous systems – a sister animal from which all other animals evolved. The polymetallic nodules are their cousins, also originating around 500 million years ago. We want to collect these metals for car batteries and laptops that will be obsolete in 5-10 years. A blip. A millisecond. 500 millions years of growth gone faster than the blink of an eye.

I also understand the other side of the coin. Proponents of deep sea mining promise less violent mining practices as land based mining is known to affect not only more-than-human species, but is deeply toxic and catastrophic for the impacts it causes human populations as well. We are at an impasse – we must choose the lesser of all evils. It is our climate reality.

While stowed away in the Bodine Lab each night on the shores of Lake Okoboji I felt quite far from the deep sea creatures I am pine over, yet I also felt quite close. Surrounded by a community of environmental students, teachers, and enthusiasts I am reminded of the warm hum of impassioned researchers, studiously forging ahead despite the bleak horizon. Studying environmental studies, sciences, etc. is not without emotional toil – the constant knowing of the climate crisis, being mired in the mess we have made of the earth elicits a very particular type of grief, one that I remember all too well from my undergraduate studies. One that has persisted throughout my life and work. Yet it also invokes hope that in community we might make a difference, or at the very least that we will not be alone in our winless quest to right global eco-social wrongs.

So, my land ethic has shapeshifted and calcified. It has morphed into a deeper and more nuanced tapestry that contends with gray areas, lesser evils, and as Haraway describes, an understanding that we need to ‘stay with the trouble’. It is not only a land ethic, but an ocean ethic, a sky ethic, and a space ethic. It touches all of the realms humans touch and more, and seeks to consider the points of view of all other things that live. It thinks in entanglements, in assemblages, in reciprocity. It knows the fireflies at Lakeside Lab are not disconnected from the vampire squid of the deep ocean, that in the beauty of this place I can see the beauty of all places, and to care for one place is to care for us all.

Walking back from Bodine at 11pm.

I have returned to LA and I will finalize the piece I made during the residency, and continue making within this body of work, much of which will be exhibited at AltaSea’s Blue Hour, an exhibition and conference on the futures of the oceans this fall in San Pedro, CA. I carry a newly catalyzed ethic with me, and aim to share it in conferences, as an instructor at UC Irvine, and as an artist and artistic director in the greater Los Angeles area. Let an ethic of care spread like wildfire, to quench the ashen ground we have laid. Let us create a new ocean ethic and act with the lesser evils in mind.

Open Studios at Lakeside Lab AIR.

Isabel Beavers

www.isabelbeavers.com

@isabelbeaversstudio