Names

by Naomi Friend

I jumped in with both feet.

That is, I left on a three day trip with the Ichthyology class hours after I arrived at Iowa Lakeside Lab to begin my two week residency. I was last-minute invited along with Neil Bernstein’s fishes class to Northeast and Southeast Iowa to do some sampling in different types of rivers, streams, and marshes. The class had already covered the shallow warm streams of the area surrounding Okoboji, the Northwest corner of the state. Now we would see the cold-water species of the Paleozoic Plateau (Driftless area) near Decorah and the warmer water types found in the floodplain of the Mississippi river south of Muscatine.

Mackenzie, Jamie, and Colton poised on a riffle in the Turkey River, ready to catch fish.

The welcoming group, only three students (Mackenzie, Colton, and Ryan), one intern (Jessie), and Neil spent the first part of the drive giving me some broad overviews. Iowa is broadly split into two parts: the area that was covered by the glaciers and the area that wasn’t. Glacial drift, or the soil, gravel, and rocks that fell out of the glaciers as they melted, is what forms that familiar landscape of gently rolling hills and rich soil covering most of Iowa.

The typical flat or rolling Iowa landscape made of glacial drift, or the rocks, sand, and soils that fell out of the glaciers as they melted.

The Paleazoic Plateau (or Driftless area) in Northeast Iowa near Decorah is not covered by much of the glacial drift that we see in the rest of Iowa. The rocks are still frozen inside from the ice age, and the springs that emerge are ice cold.

An Algific Talus Slope near Edgewood, IA which offers a unique cold micro-climate.

After about three hours of driving, this is where we took our first sample. We piled out of the van above a riffle on the Turkey river south of the small town of Cresco.

Ryan and Neil working with the electroshocker to collect fish samples.

Though I technically didn’t get my feet wet, this was my first scientific field experience. I felt pretty excited and only a little afraid for my cameras as I hauled the waders up to my armpits.

The students unrolled the seine (don’t call it a “net,” no one will know what you mean) and shouldered the electroshocker. We carefully entered the fast, cold water, testing the footing to avoid slipping on algae covered rocks. Soon enough, we had our first samples – Shiners, Suckers, Minnows, a Golden Redhorse, and more. Mackenzie assured me that the fish weren’t in fact dead, only stunned, which allowed them to be caught and observed before being released. In the past, fish have been collected and taken back to the lab. This approach was both nicer for the fish and valuable for the students, pushing them to learn in the field.

The Seine is the net used to catch fish as the travel downstream. It takes a lot of leverage to hold it against the current.

I was amazed to see shiny slippery fish bodies emerging from the dark fast water. Fish are something that I know are there, but they remain invisible, submerged in their watery life. With our gear we able to take a snapshot of who is living under the surface. Not only were there fish, but there were many kinds of fish. Are the scales tall or long? Are they spotted? How many scales between the pectoral and pelvic fin? Does the mouth point forward or down? Do the eyes face forward or to the side? Where is the anus? I had never thought of any of these questions, but the students had, and were able to name many fish with only minimal prompting. When they got stuck, the students referenced the field identification book. Neil confirmed when they had arrived at the right answer.

A beautiful Rainbow Shiner.

A few of the fish we caught near Cresco.

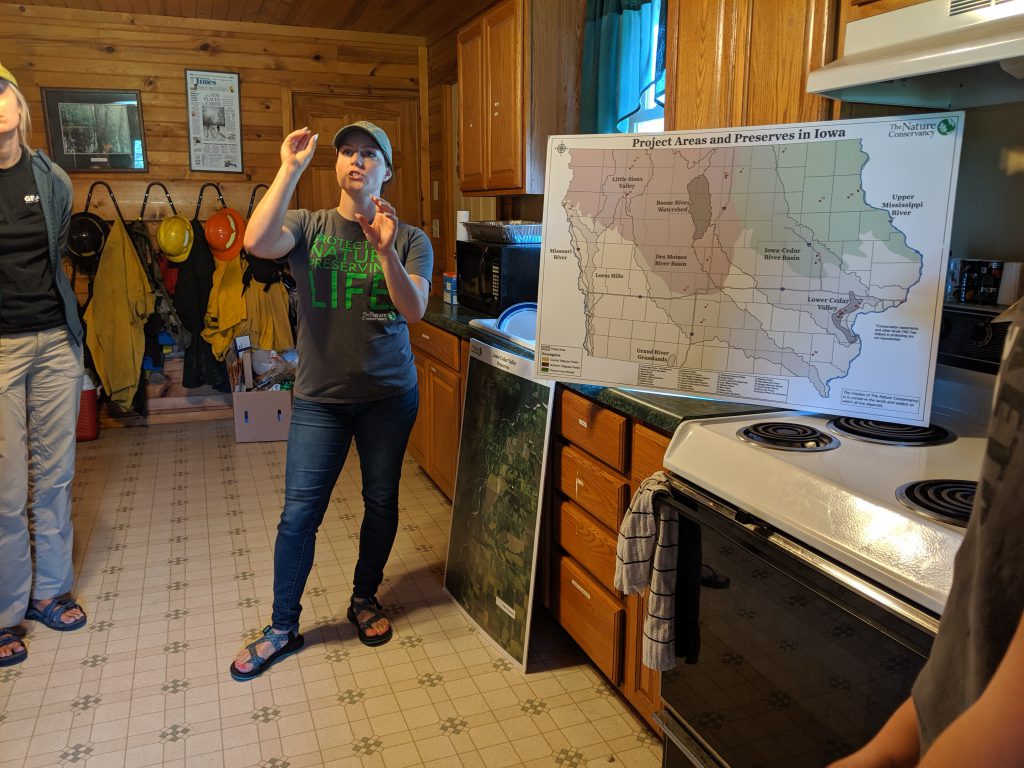

The next few days brought trips to the Nature conservancy in Southeast Iowa to look for warm-water fishes in the Mississippi floodplain. The Nature conservancy strives to protect and reclaim farmland for preservation purposes, normally land they buy is no longer suitable for farming due to regular flooding. The Letts chapter of the Nature Conservancy currently manages 4,000 acres with a mere 4 employees, only two of which are full-time. With so much land to manage and so few resources, attention is given to the most biodiverse areas. Cows are used to graze the invasive species and volunteers or students are brought in to do much of the observation and cataloging.

Our guide Hannah Howard from the Nature Conservancy explains the geologic history of the Mississippi floodplain and its unique characteristics.

With their work, the endangered Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid has flowered for the first time in living memory in a new section of Nature Conservancy land, and a colony of pale green orchid was found. We stepped through a patch of endangered Whorled Milkweed on our way to sample a low wide pond.

Mackenzie and her large Bowfin found on Nature Conservancy land, the Land of the Swamp White Oak Preserve. Photo by Hannah Howard.

At every new location and sample, my mind was soon swimming with names. Names of rivers. Names of landscape characteristics. Names of plants. Names of fish parts and the fish themselves.

With each name, I saw something I hadn’t seen before.

I was reminded of the Biblical story of creation. In the narrative, Adam was tasked with naming all the creatures of the garden. Naming invites observation, reflection, and ultimately love and appreciation each individual for its unique characteristics. The story tells of a people tasked with the creative act of responsibility and care. The students were learning the art of naming: both the names that are already given to the fish and why they are important. The names of the fish open doors to understand the health of the streams, the type and origin of the water, and what needs to happen to maintain the balance of life here.

Sampling Twin Springs Creek in Decorah in the Iowa River Basin.

I couldn’t help but reflect on that story of naming the creatures and charge to humans to care for the land as we returned to Lakeside. I had learned quite a bit about the landscape, geology, and history of Iowa, and the qualities that make for a good and bad habitat for its fishes. Because of this, I saw the landscape in a new, exciting way. Each seine full of fish brought the possibility for a new unseen species. Would we see the rare Grass Pickerel? Ozark minnow? Orange Spotted Sunfish? As we squelched through muddy forest floodplain, would we spot a Central Newt under a rotting log?

The Orange Spotted Sunfish gaping in the muddy water, streams choked with runoff from the spring flooding. Photo by Hannah Howard.

We did find a Grass Pickerel and an Orange Spotted Sunfish. The fish in this particular body of water were in particularly bad shape, and one spot we sampled could not support any fish due to lack of oxygen in the water. We were not able to find the Ozark minnow or Central Newt. Their numbers have decreased due to their sensitivity to agricultural runoff and flooding. I hope water management improves in Iowa soon. We have a responsibility to these creatures, their ecological community and to ourselves. With the Naming comes understanding, and the power of creative solutions that both support agriculture and biological diversity.

We found a federally endangered species, the Iowa Pleistocene Land Snail, on the Algific Talus Slope near Edgewood, Iowa. They can only live where the rocks remain chilled from the last ice age in the Paleozoic Plateau of Northeast Iowa and were believed extinct until a live snail was found in the 1950’s. This was the most surprising and exciting part of the trip for me. The microclimate that supports the snail’s delicate ecosystem is in danger of melting away as the climate warms.

Developing a cyanotype print in a cold, springfed stream in the Driftless area near an ice cave by Edgewood, Iowa.

A cyanotype of Ferns in Bixby State Preserve.