Artworks inspired by Animal Behavior

by Richelle Gribble

“We can allow satellites, planets, suns, universe, nay whole systems of universes, to be governed by laws, but the smallest insect, we wish to be created at once by special act.” — Charles Darwin

During my two-week residency at the Lakeside Lab AIR, I made a series of creative projects inspired by site-specific findings. Located alongside West Okoboji Lake, the lab is home to diverse species thriving in an abundant ecosystem. I created three art projects based on my experiences in the research labs and on the field.

Project 1: 3D-printed insects based on insect collection.

Moth collection at the Lakeside Lab AIR. Photo Credit: Richelle Gribble

Iowa Lakeside Lab contains an enormous collection of plants, algae, fungi, insects, and birds. Hundreds of species are classified, labeled, and stored for scientific research. Stacked in drawers and cabinets, there is vibrantly-colored wildlife dating back to the late 1800’s. Most of the collection is from West Okoboji and nearby regions, showing impressive biodiversity of the local area.

I closely examined the cataloguing process. Here, I learned about how each organism is labeled and preserved. The collections of organisms made me realize why they matter. Some of these species are threatened or endangered, and one of the few records of their physical presence is modeled in these collections. Why do we need to record the past? How else can we preserve what has lived?

3D-printing insects and archiving collections. Photo Credit: Anna Polonyi & Richelle Gribble

3D-printing insects and archiving collections. Photo Credit: Anna Polonyi & Richelle Gribble

When considering how to archive species with dwindling populations, I thought to recreate the collections made from a material that outlives all of us: plastic. Plastic fills our land and sea, impacting Earth’s inhabitants at a global scale. It is the cause of death for many species. Yet, in terms of preservation, it has similar uses to that of the arsenic in the laboratory — it can make the presence of these plants and animals timeless.

Plastic copies of Bombus Pensylvanicus. Art by Richelle Gribble

I recreated the collections using a 3D-printing pen. I traced and mimicked the volume and forms of dozens of insects. The length of their bodies matched those preserved in boxes, wingspan taking on a similar shape. Hand-written labels were placed to identify the plastic insects. They were arranged in groupings much like that of the real collections. This process taught me about the structure, anatomy, and names of each insect.

Insect chart made from plastic. Art by Richelle Gribble

Then, I photographed the plastic insect charts. Image software enabled two focusing mechanisms, generating images of foreground and background meshed together into one detailed image. A colorful grid and measuring system was placed next to the charts, just like the real collection photos.

Butterfly chart. Art and image by Richelle Gribble

“I wanted to know the name of every stone and flower and insect and bird and beast. I wanted to know where it got its color, where it got its life — but there was no one to tell me.” — George Washington Carver

Dragonfly chart. Art and image by Richelle Gribble

Project 2: Firefly simulations on mobile devices.

: Sample clip of “Firefly Simulations” video project. Art by Richelle Gribble

In Iowa, I encountered fireflies for the first time. Pitch dark, the constellation of glowing bugs circulated in the grasses. It felt like I was floating in the stars. I was captivated — deeply entranced by the fluidity of motion and graceful gestures. I studied the ways they moved, watching lights synchronize and scatter, again and again. This transcendent experience among the fireflies manifested itself into an auditory and visual project using smartphones.

Fireflies on the field. Photo Credit: John Starks

To recreate a similar experience of my memorable sparkling night, I made an animation with scattered light points. These dots undulated in chaotic ways, falling in and out of synchrony. This visual was paired with syncopated and unified soundscapes. When flashing light points and audio synchronized, the entire screen flashed as one light.

This video, Firefly Simulations was then shared with all staff, students, and scientists at the Lakeside Lab. We gathered outside at night where many fireflies moved about. Here, I invited all participants to play the video on their individual smartphones at the count of three. As sounds and lights illuminated dozens of digital screens, I told participants to find those in the crowd who’s lights flashed at the same time.

Mobile phone firefly simulations. Photo Credit: Richelle Gribble

It was incredible to see a burst of energy erupt as people began pairing, finding the flashing lights that matched their own. People were so excited when their sounds and lights synchronized. After this collaborative video display, we discussed how it mirrored the behaviors of fireflies.

Synchronizing light and sound, mimicking fireflies. Interactive art by Richelle Gribble

Synchronizing light and sound, mimicking fireflies. Interactive art by Richelle Gribble

Synchronizing light and sound, mimicking fireflies. Interactive art by Richelle Gribble

Fireflies use bioluminescence for sexual selection. They synchronize their flashing lights when in large groups in order to attract female fireflies. This is a mating process to select potential mates. As these bright lights appear even brighter in groupings, moments of synchronicity occur. It was exciting to demonstrate this natural phenomenon in the presence of fireflies buzzing about.

Project 3: Creating artworks inspired by field journals.

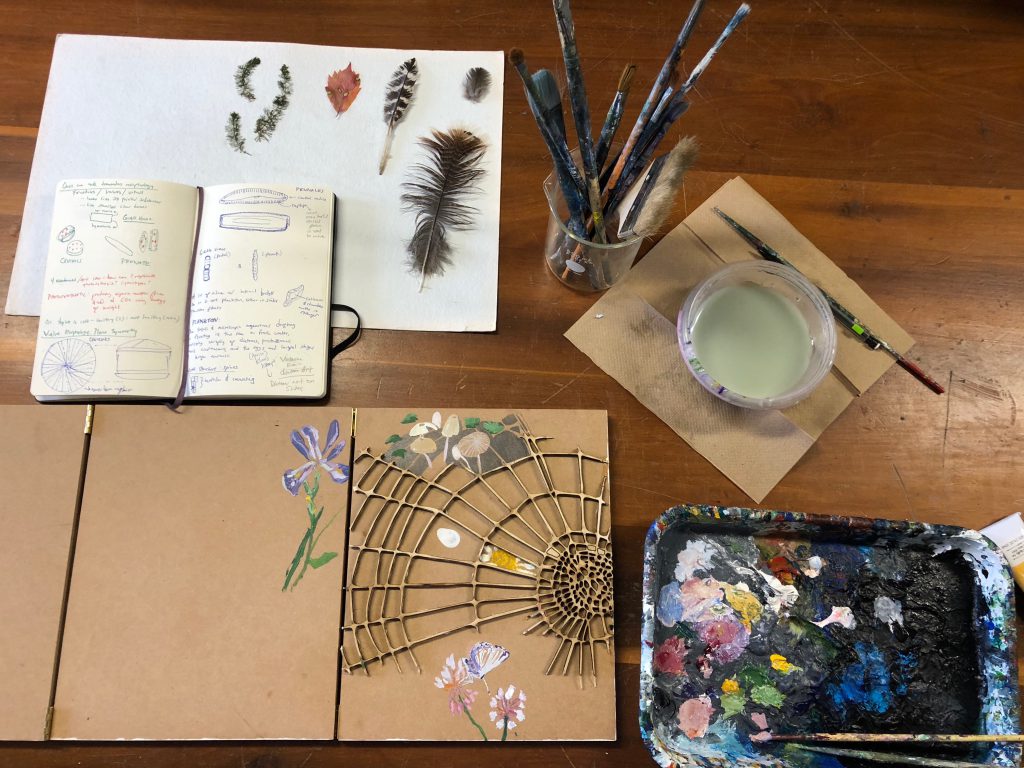

My final project was a mixed media field journal. At this residency, I learned that illustration is a very important tool for field research. I never realized how often scientist are making sketches in their notebooks. I observed how they drew during classes and field trips, recording and labeling their observations.

There is an incredible loose yet specific drawing style that takes place. It is urgent, expressive and fleeting but also so detailed. Although few are trained in drawing, it was interesting to see how they visually interpreted their encounters. Nature journaling and field notes require intensive observation skills, taking in as much visual information possible before the subjects moves or the outside conditions change.

Field Journal by Richelle Gribble

“The first law of ecology is that everything is connected to everything else.”― Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

Acrylic paintings on field journal. Photo Credit: Richelle Gribble

Some illustrations were very intricate, colored to match the studied subject. Others were partially completed, documenting the general idea of the perceived organism. Often times, the subject was illustrated in pieces at various angles, notes scribbled nearby. Inspired by the quality and function of these illustrations, I was inspired to make a field journal of my own.

My field journal took form on panels of wood hinged together into an accordion book. I adhered laser cut pieces of a wooden spider web onto each panel. My goal was to illustrate the species we observed into the web structure, referencing the web of life of West Okoboji. This project is not yet complete, but I will continue to add the names and illustrations of plants and animals witnessed in Milford, IA.

Open Studios at the Iowa Lakeside Lab. Photo Credit: Richelle Gribble

To conclude my residency, these projects were featured in an Open Studio showcase. Student, instructors, visiting scientists, and the local community gathered to see the displays. It was a rewarding experience to show them how I visually translated our joint research and discoveries.