Uncommon Ground

by Jenie Gao

For more than 5,000 years, tallgrass prairies occupied 240 million acres of North America’s landscape, about 85% of the Midwest. All of this changed in the 1800s with European settlement. Settlers arrived with the goal of “breaking the land,” to replace the rolling prairies with productive farmland. They succeeded, and today, from region to region, corn and livestock cover the landscape. About 1 to 4% of America’s original prairies remain.

Standing on a remote slope in Loess Hills, surrounded by swaying grass all the way to the horizon, it’s hard to imagine that the untouched wilderness doesn’t just keep going. The Loess Hills were formed in the last Ice Age, when the weight of the glaciers ground the boulders below into a fine dust. When the glaciers receded, wind picked up the dust and stacked it into terraced land formations that are known today as the Loess Hills. The only other geological formation that resembles this region is in Mongolia. As infinite as the Hills seem, just down the trail is the paved road, with power lines cutting through the prairie. Suddenly, the wide expanse of land also feels rare and small, like a hidden gem. The settlers came in the 1800s with the goal of breaking the land the way one would break a plow horse, shaping its instincts and labor to serve the production needs of humankind.

It is often said that artists mirror society, from its ills to its joys. In times of freedom and learning, the arts explode with creative expression and discovery. In times of fast commerce, the arts embody brands, commodities, and decorations. In times of grief, the arts offer solace and empathy. In times of fear and fascism, the arts become the ward of propaganda, and eventually, uprising. Throughout the times, the arts nearly always represent the uncommon: from rare prizes and possessions to the invisible and underappreciated, from uncommon viewpoints to a new way of thinking.

I have often thought of my artwork like a “Modern Day Aesop,” a vessel to tell stories and teach lessons about the dilemmas that face the modern day human, caught between human-made systems and nature’s ecosystems. I am a research-intensive artist. The things I study reappear and evolve in my work for years to come. In the past few years, I’ve worked hard searching for ways that different stories connect and what could be the “common ground” between polarizing and even divisive topics. I’ve sought ways to create a paradigm shift among commonly understood things, not to eradicate what people know, but to adjust the lens through which people look at the world.

But in the past year, I have found this “common ground” to be harder to find and harder to protect. Political conversations quickly turn bitter in people’s mouths. Either-or dichotomies get stronger. Diversity and inclusion efforts meet with insecurity, resistance, and turf wars. The divide between what two people see can be so vast, to the point that two neighbors can seem to have grown up on two different planets. No bridge can close a gap where walls and obelisks obstruct the way. Slowly, I have come to wonder if perhaps what we need isn’t reconciliation (or appeasement) of opposing forces, as much as protection and cultivation of that which is increasingly rare.

In the past two weeks as an artist-in-residence at Lakeside, I have found myself immersed in a myriad of examples of habitat loss, restoration, and protection. I went bird banding with Neil Bernstein’s ecology class, to learn about the population of purple martins. The colony we visited lives in human-made housing at the Bird Haven. Purple martins, like those living in this colony, have suffered in the face of competition from invasive house sparrows introduced to the area by European settlers. The sparrows destroy the martins’ eggs and take over their nests. The purple martins have learned that if they build their nests in human-made housing, they will get the added benefit of human protection from the sparrows. In a way, the martins have now become dependent on human-provided housing and guardianship.

From scientific study to artistic representation

Sometimes, I wish I could be more objective like a scientist. But as an artist, I can’t help but build subjective narratives. Hell, during my time at Lakeside, I “adopted” three tiger salamander tadpoles and named them after the Three Fates: Clotho, Atropos, and Lachesis. They shared a tank in my studio with a leech named Hydra, a diving beetle named Hercules, and a scud bug called the Nemean Lion. Over the course of a week, Clotho devoured almost everyone, including Lachesis. I was quickly down a demigod, two mythical beasts, and a fate. Out of mercy, I separated the remaining two tadpoles, but I have yet to figure out what it means when one of the Fates consumes another.

Greek mythology aside, my job as an artist is to make people feel something, and people feel based on what they can identify with. So I draw parallels between the lives of purple martins and different populations of people—from the Native Americans to the poor—that have always been forced to move in the name of economic development. Below every brand new freeway there is usually an affordable housing unit and new charity service. Inevitably, treaties change, and the work necessary to protect the disenfranchised will continue however it can. I am grateful when I see examples of human stewardship, to conserve the resources we have, to restore the habitats we’ve destroyed, and to improve the practices by which we live off the earth. I also can’t help but recognize the vigilance required for peace, the activism needed for conservation. Iowa Lakeside Laboratory is approximately 150 acres of protected land in the face of the never-ending push for human development. The first line of defense for any nature reserve is education.

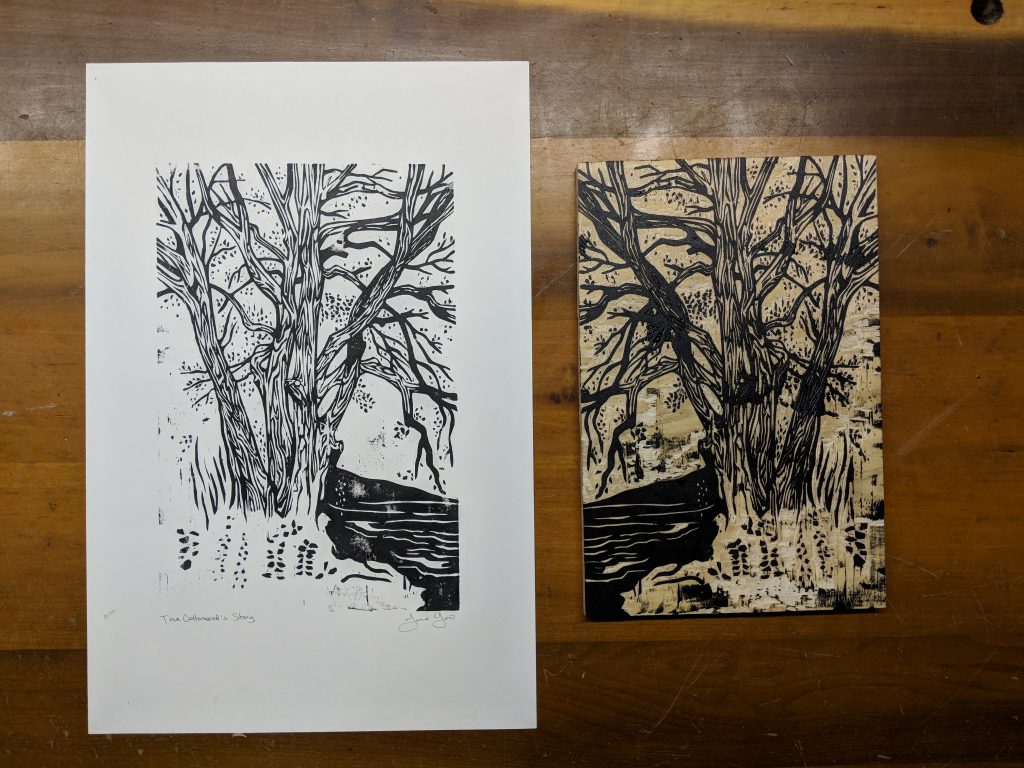

Coming back to my studio practice, I find myself wondering what the conceptual significance is of each action in the creative process. When I draw, my job is quite literally to make things “look good” on paper. When I carve, it is almost like I am excavating. I am cutting pieces out to create something new, and I have to go deeper to see what arises to the surface. In all artistic work, I am making a record that previously did not exist. In the making of something unique, one-of-a-kind, and decidedly uncommon, I am hopefully bringing forth an idea that others have not considered, yet can identify with. In creating and honoring the uncommon, the common and the universal has a chance to come together.

I joined Paul Weihe’s class to study the cottonwood trees along the lakeshore by Lakeside Lab. The closer the trees grow to the water, the more likely they are to have multiple trunks instead of a single, central trunk. These are cottonwood trees like all the others, made different only by their growth response in a unique circumstance. The trees by the water have, for some reason, chosen to spread out instead of grow tall. Paul theorized that the trees by the water “choose” to spread out to have broader leaf coverage. Since fewer trees are by the water, there is less competition for space, therefore less need to grow tall in order to reach the sunlight. One of the other instructors, Lori Biederman, had a different theory. She thought that the trees on the shoreline might get a shock in their roots when the water freezes over, and that this shock would cause a division in the trunk’s growth. Regardless of their growth strategy, it’s worth noting that trees grow everyday until the day they die. There is something poetic about know that it’s possible to grow forever, through diverse means.

Artists and scientists alike are observers who collect and record information to better understand the world around us. Perhaps the biggest difference would be intent. Scientists do not assign intent to nature—nature isn’t cruel or merciless. Nor does nature decide or choose the fate of one species over another. This is important, because it maintains a framework to study the world fairly and objectively.

Meanwhile, artists assign more than intent. A heartbeat is more than a physical action; it is a poem about life. The heartwood of a tree is more than the hardened, mature wood of a trunk that stabilizes the tree’s structure; it is emphatically the center, the reason a tree keeps standing. The deep roots of big bluestem and other native prairie plants do more than create channels for groundwater; by preventing erosion and flooding, they literally and metaphorically hold the earth together.

It’s almost impossible to imagine what it was like when 240 million acres of rolling prairie grass dominated the North American landscape. For all we do to protect and restore what we have of the natural landscape, we have already decidedly changed it, and will continue to do so however we decide to live beside nature. But maybe the more we understand natural environments, the better we can respect their boundaries, as entities in their own rights, not for us to tame or even find purpose in. At the same time, we can find what it means for us to be stewards, community citizens, neighbors, or any other term that calls us to the service of doing better. We can understand the ways in which the environment is both distinct from us and integral to us, the ways in which we are independent and interdependent. More and more often, I notice when the median in a road has been replanted with prairie grass or with a rain garden, when native grasses start taking over neighbors’ lawns. These are small efforts yet, and uncommon in the face of how most people and places maintain their lawns. And because they are still uncommon, they are worthy of attention and investment.

[