Testing the Waters

by Parts Per Million Collective

We started Parts Per Million Collective to change our understanding of art and art making. We feel art can and should begin to take a more active role in the climate crisis. To us, this means creating works to directly benefit the environment. Our pathway to this goal is through research, testing, and merging carbon collection technology into public artworks. In this way each artwork serves double duty, as advocate and as activist. Our Parts Per Million Collective project at Lakeside was to develop a sculptural floating algae bioreactor using a buoy system developed several months earlier. We also wanted to test our newly developed buoy system under environmental conditions for the length of the residency. As a collective we follow specific self-imposed tenets to guide our decisions and practice. These rules include using recycled/up-cycled material as often as possible, researching and implementing the least environmentally damaging practices, and striving for our sculptures to eventually net zero emissions. Our tenets were tested at Lakeside as our time was short and goals high. As a husband/wife collective with a family we split our time at Lakeside into one week sessions, overlapping for a few days to collaborate on the direction of our project and goals while also entertaining our children at Lakeside and Okoboji. While this approach wasn’t ideal for a fully collaborative two week residency, it did allow each of us to approach our shared goals independently, relying on our individual artistic values and practice to guide us individually. Below we’ve reflected on our time spent at Lakeside individually.

Edward: I arrived at Lakeside Lab with two artistic directions to pursue. During the previous winter while working with Drake University students we developed the SPARCC (semi-passive algae rooted carbon collection) buoy. The first goal at Lakeside was to simply test how well the SPARCC buoy worked in a natural setting over a set amount of time. The second was to begin merging the design into our artmaking practice. I knew upon arrival that Lakeside was going to be a wonderful challenge in an idealistic location for the next two weeks.

The first few days at Lakeside were spent getting the initial SPARCC buoy ready to be tethered off the boat dock and exploring the surrounding area for material. I had brought along some old buckets and other previously sourced material to create more carbon collecting buoys and planned to utilize material sourced from the surrounding area to create our floating sculptural carbon collector using the technology set forth in the initial SPARCC buoy. I anchored the SPARCC buoy off the dock with a small culture of spirulina in the upper chamber. Samples taken on the first day (148 ntu) and the last day (262 ntu) show an approximate 15% growth rate per day. One of the benefits of the SPARCC system is algae’s natural ability to cleanse water of excess nitrates during growth. However Miller’s Bay doesn’t have an excess of nitrates; great news for the water ecology of West Lake Okoboji. I do expect a greater growth rate in waters that experience this issue. I was happy the culture and the buoy survived for 10 days in the lake water, giving us hope that as we scale up for larger installations the algae will thrive in the buoy.

During my time at Lakeside I often explored the area by bicycle offering me some time for reflection. Lakeside is a place within a place. It seemed that Lakeside itself acts as a quiet anchor of experimentation and exploration in respect to its natural surroundings. A place of reserve and reverence for the natural world and all it has to offer. By contrast it’s nestled amongst a bustling tourist economy filled with people enjoying nature and its benefits in a more celebratory manner. There’s a meaningful and beneficial coexistence or reliance that’s struck between these two places.

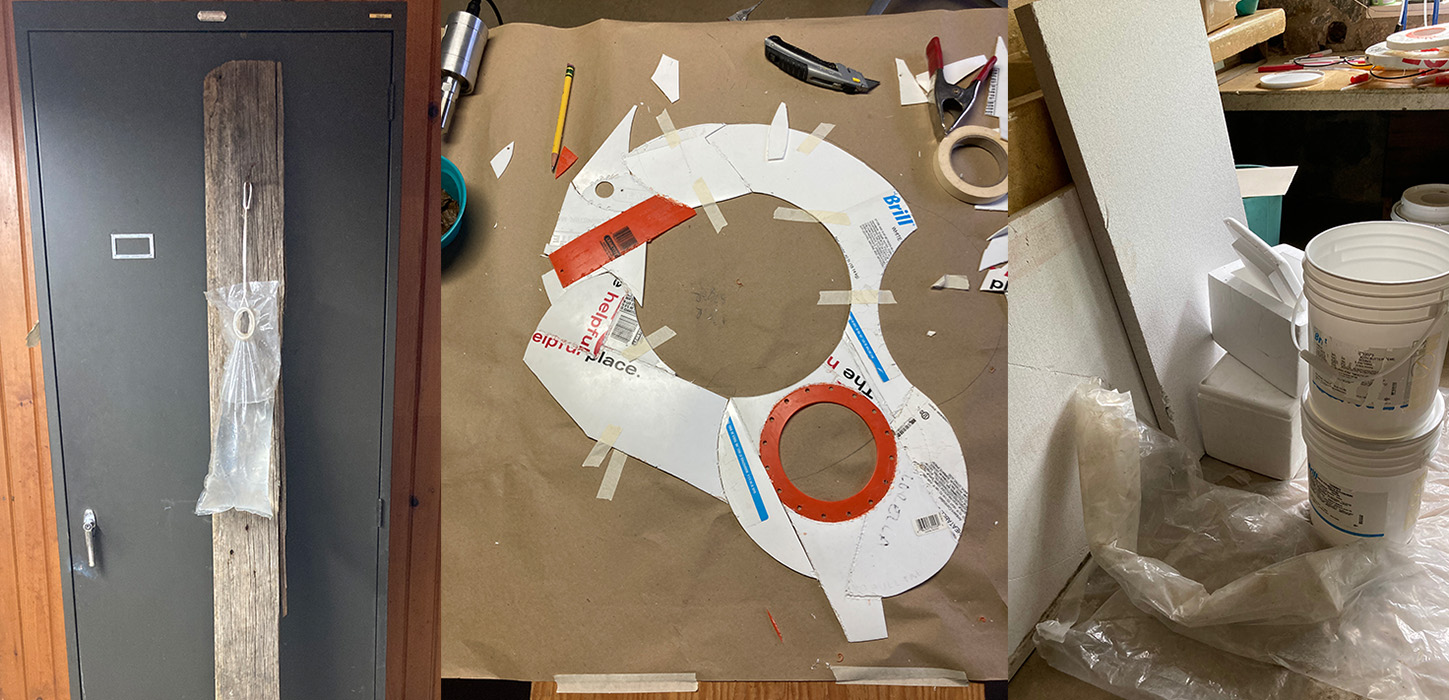

With the first goal in the water I began to focus on finding materials for a more artistically driven bioreactor. I’ve always enjoyed exploring material unknowns and it often feels like the answer is just beyond the next experiment or discovery. I started searching around the immediate areas, along the trails, canoeing along the lake shore, moving along the bike paths and eventually through nearby neighborhoods and parks. There was some time spent welding found plastic sheeting into bags to house small algae cultures. I enjoyed this process and there were some interesting experiments but I could never seem to nail down exactly how they worked visually. I eventually found a couple of buckets in the muck. Adding these to a collection of buckets given to me from the helpful people at the local HyVee bakery, I started making something I thought could float. I cut and welded the bucket plastic to create a series of shaped floatation rings that would support the buoy in the water. Over the phone Emily and I discussed approaching the water surface as a sort of drawing plane. Utilizing the flotation rings of the buoys to create a kind of drawing seen from above. I was able to create 3 different shapes from the buckets I had. Connecting them into a more cohesive shape would have to be the place where Emily picked up. I made a habit of continuing to search out material throughout my time so Emily might have enough to work with. Aside from the collaborative work I would also be returning home with a number of concepts and ideas from my own research and through experiencing the various events and people working and learning at Lakeside Lab.

Emily: I arrived the following Sunday to pick up where Edward left off. With the raw materials Edward collected I began working to transform them into a sculptural buoy. Because Edward found so much foam- multiple foam coolers and large sheets of foam-we decided to utilize this buoyant material first. This material was difficult to transform without creating a TON of foam saw dust. The wasteful bi-product of carving foam weighed on me as I worked out the first idea I had. How does making a sculpture by producing micro-plastic waste help the environment in any way? Logically, I know that the full sheet of foam we found in a dumpster would break down into tiny pieces in a landfill eventually, but the very real image of my hands creating the mess was enough to pause my idea of carving the foam into a form. Instead, I decided to rethink using plastic cut offs from buckets (once containing frosting and smelling sickly sweet) to continue our plastic patchwork edging. By piecing plastic sheets together I was adding structural integrity to the edges of the sheet foam, the process similar to piecing a crazy quilt. I noted that looking into more sustainable buoyant materials would be a priority for further research after Lakeside. By phone, Edward and I discussed some avenues to take with our buoy, deciding on using the foam as a large “island” in which to attach three SPARCC bucket buoys. I continued altering materials for the buoy including braiding 25’ of “rope” out of a plastic mattress bag Edward found on the side of the road.

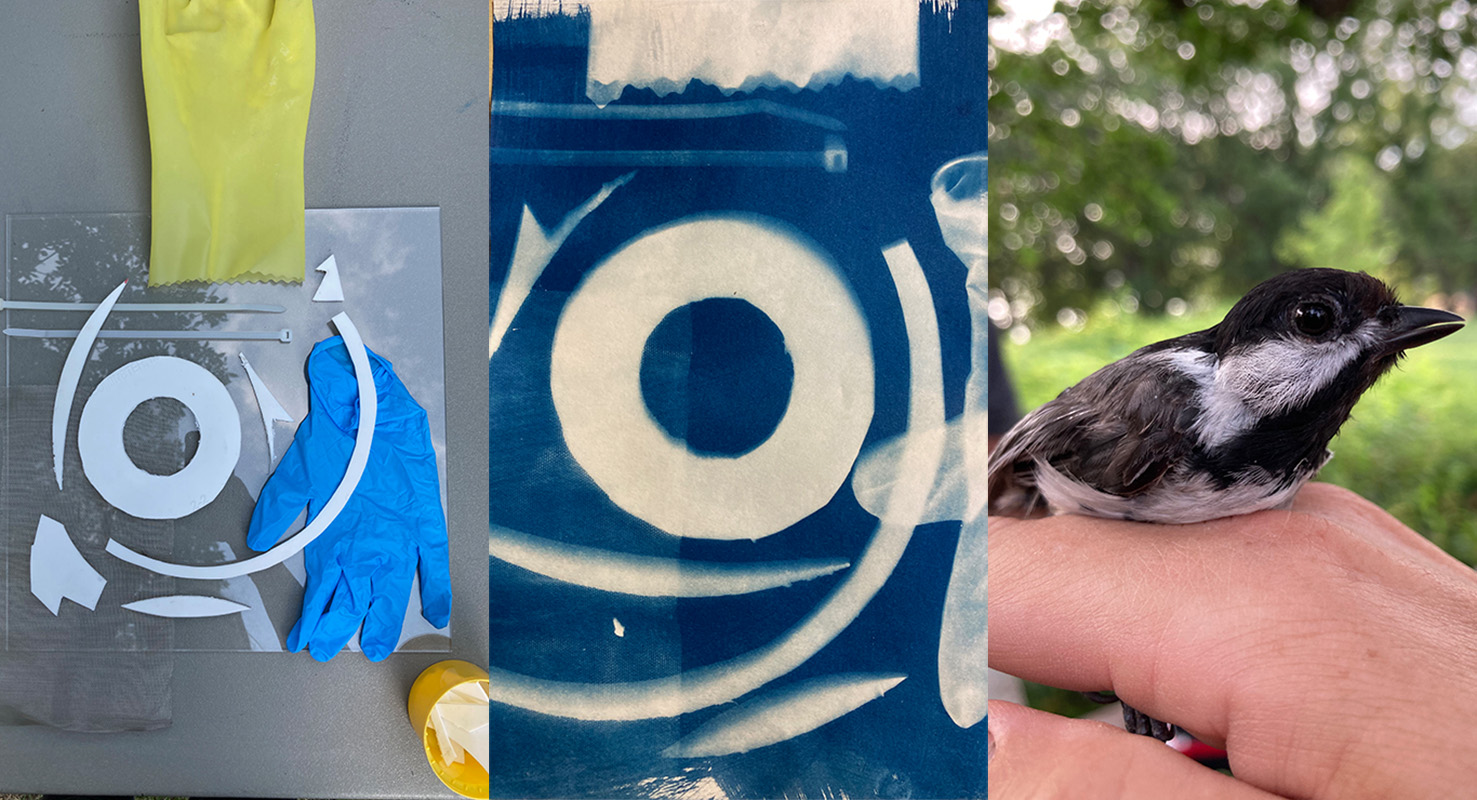

When not working in the Bodine studio I was able to participate in some workshops and join in on classwork. I made a cyanotype, using found plastic objects in my environment. I banded birds, listened to the EPA Region 7 field team discuss their efforts to document stream water quality in Iowa, heard a writer in residence recite their poetry, and I learned about faculty scholarship and research at Lakeside during our many meals shared together. At dusk, I watched the turkeys fly to their roost in trees at the edge of the bay and mapped the fireflies with pencil and paper at night.

On Friday, I finally finished the SPARCC island. I used a kayak to drag it through the vegetation on the north end of Miller’s Bay and let it float for a bit. We already knew the individual buoys would float, but with the addition of a large foam sheet the possibility of wind flipping the island was a reality. Thankfully, the island stayed flat, although I’m not as convinced of its stability in high gusts and rough water.

We successfully created a new buoy during our residency, a goal we both had. We also were able to test a previous design for the full two weeks. But, more than our stated goals, I learned more about my individual process and how it should be utilized within the collective. As an artist who generally uses time and craft to give value to trash, I have to remember my practice, no matter what I’m making, is slow. As an artist who individually works small scale, working large scale requires me to think differently about the visibility of my handwork 50 feet away from the shore.

Our time at Lakeside allowed both of us to find our individual approaches to making together. It granted us time away from the responsibilities of family life to focus on our collective goals. And it allowed us to connect with others while refining our ideas about the responsibility of art and science today.