The Prairie Flower and the radical nature of experimentation

by Jenna Bonistalli

To the being fully alive, the future is not ominous but a promise; it surrounds the present as a halo. It consists of possibilities that are felt as a possession of what is now and here. In life that is truly life, everything overlaps and merges. – John Dewey

Our word radical was formed from the Latin adjective radicalis, which simply meant “of or relating to a root.” The Latin word radix meant “root.” In botany, the first part of the seedling to emerge from the seed is the embryonic root of the plant: the radicle. This seems relevant when considering the nature of a prairie’s extensive root systems, many of which extend downwards up to 15 feet. These native plants improve soil’s ability to infiltrate and absorb water, reducing run off. Deep roots anchor soil and decrease erosion. They create a strong, stable ecosystem for wildlife.

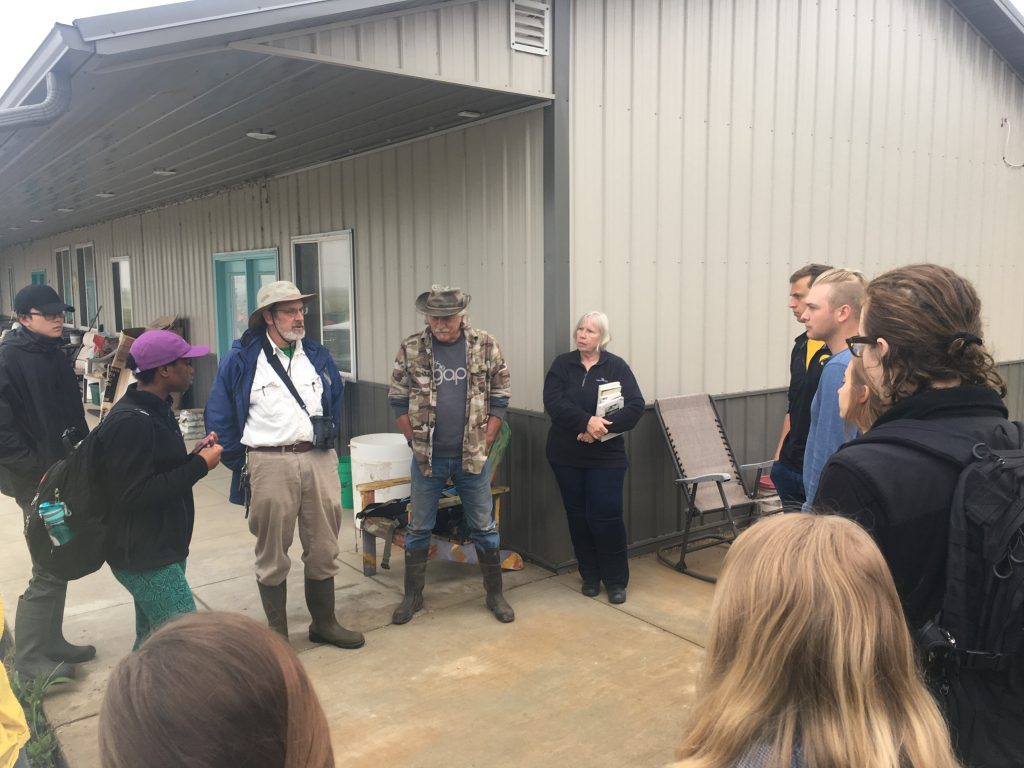

On Monday, I joined Neil Bernstein’s Ecology class on a field trip to visit Dwight and Bev Rutter on their farmland, to learn about the alternative approach they have taken, particularly in their efforts around The Prairie Flower, a native seed and plant nursery.

The first room we see is the “de-bearding” area, where Dwight gracefully explains, “It takes 4 years to learn how to harvest each plant.” He describes in detail some of the most efficient and effective discrete processes for harvesting the seeds of over 45 species of native, perennial plants they grow. It’s amazing. And revolutionary. This area of Iowa is farm after farm – soybeans and corn after soybeans and corn – and Dwight and Bev are doing something really, really different.

Before 1800, Iowa was surrounded on all 4 sides by tall grass prairie. The “breaking of the land” and the 1837 introduction of the steel plow by John Deere, within 25 years made Iowa the most eco-altered area in the world with the conversion of prairie to farmland. Over time, single crop monocultures of industrial farming, soil erosion, the use of herbicides, pesticides, antibiotics, as well as the presence of CAFOs, has led to dramatic ecological effects for both land and waterways.

In the early 2000s, Dwight says he got tired of the chemicals. And, on their 400 acres of land, they decided to do something different. Their main business is growing fields of native grasses, harvesting and selling their unique seeds. But, Dwight has “projects” all over the place. Rather than cultivating tall native grasses in a greenhouse, he’s earmarked a rocky area to let them propagate in the ground – 56 varieties of plants grow there – the worth of their seeds ranging from $4 to $4,000 for 1/8 lb of seeds. It’s the 3rd year of this project and having made changes to the system, making progress every year. Certain areas of his land he’s restored and planted intentionally. Other areas were farmland that he stopped farming 10 years ago, and hasn’t touched since, seeing what will happen. Other areas, for example where they harvest golden rush seeds, are 10,000 year-old land. He’s both created and restored natural waterways on the land, like an Oxbow in the river. And they have many other projects, from cultivating nesting areas for birds to sculptural pieces. He spends time on his land. He spends time with the plants and animals. He notices things. He’s seeing what’s happening. They try new approaches.

The biodiversity and the health of his land is dramatic compared to the farming monocultures that surround him on all four sides. Neil did some simple soil absorption tests with a tin can, and the results were staggering. On the 10,000 year-old land, the water channeled immediately downwards, through the rich root systems, whereas on a plot of standard farmland (outside of Dwight and Bev’s property) the water sat so long we stopped counting. It had no place to go. The prairie restored farmland was somewhere in between, the root systems and layers slowly returning to absorb water in increasingly nutrient rich soil.

I have been making paper outside many days this week. People have been walking by asking what I’m up to. There are a lot of questions about the process and how it works, as well as What are you doing? What are you going to do with the paper you make? I’ve been catching myself as I say, “I’m experimenting with a few things.” We use that word all the time in art practice. But, then I think, “These are Scientists. Can I call this an experiment?” Don’t things need to be more formal for this to be considered a proper “experiment?” As we were taught in school — you need a hypothesis, a protocol, fixed variables. There’s a distinct beginning, middle and end. More control? Detailed notes?

In webster’s the verb ‘experiment’ is defined:

1 . perform a scientific procedure, especially in a laboratory, to determine something; try out new concepts or ways of doing things — from Latin experimentum, from experiri ‘try’

One day at lunch, I was talking about this verbiage with Rebekah, a student in the Aquatic Ecology class, and she said, “you know in Spanish the word ‘experiment’ – experimentar – actually means ‘ to experience.’” Wow. Then, this begs the question, what are experiences? They are Dwight’s projects. They are the field trips we have taken over these past two weeks. They are tests with materials. They are observations of new ways of working and being. Experiences help guide us to further understand, to notice more, to make choices that are increasingly aligned with who we are and expressions of how we see or would like to see the world.

Artists spend time with materials.

We see what they can do. We try things. We interact. We discover. We experience.

Materials are part and remnant of the living world, and materiality is a language.

In his first chapter of Art as Experience, “The Live Creature,” John Dewey writes, “When artistic objects are separated from both conditions of origin and operation in experience, a wall is built around them that renders almost opaque their general significance… Art is remitted to a separate realm, where it is cut off from that association with the materials and aims of every other form of human effort, undergoing, and achievement”(3).

Here at Lakeside, I have been experimenting partly because I am working with different variables than I normally do – outside the traditional studio. These variables include – the weather, systems for drying, even the type of fiber and equipment. Once a variable changes, I have to try new approaches to see what will happen with the material. I have a good guess as to how things might behave, but there are many things I’m not sure of. And, there are aesthetic choices in the final result I might not be able to predict without trying different approaches.

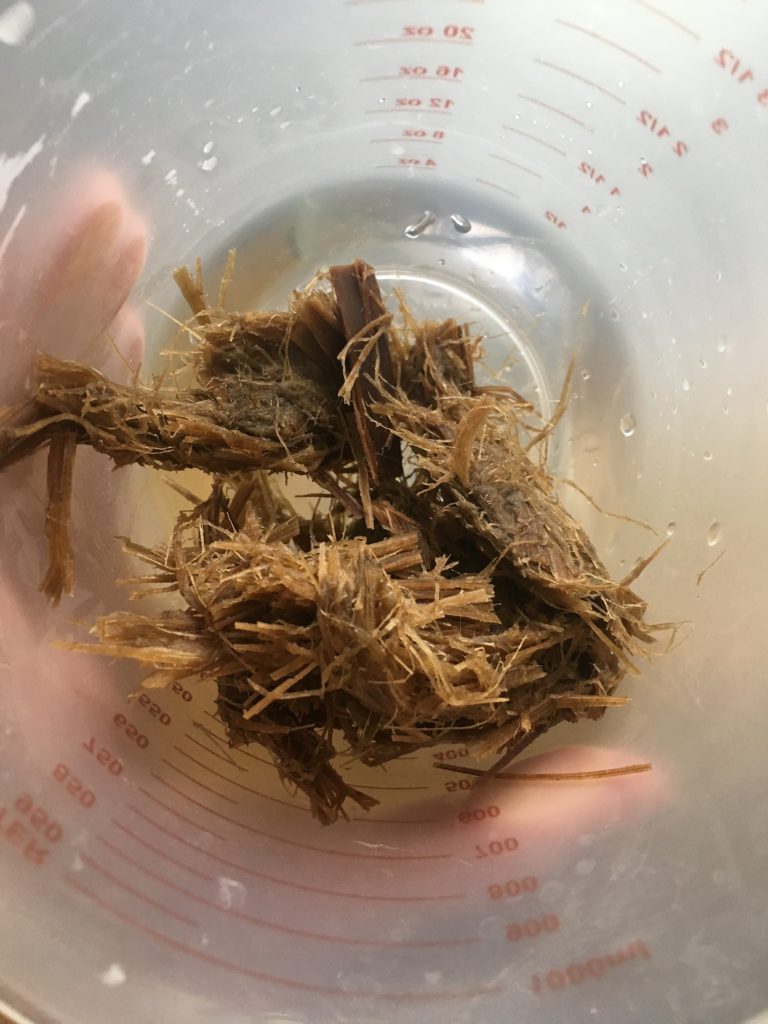

Per Neil’s encouragement and curiosity, we made paper with cattail leaves and fluff harvested on Dwight and Bev’s farm. Is this an experiment? Well, I will say yes, because I had never done it before! I can begin by reading about other people who have done it before (which turns into a hypothesis that encourages me it’s possible). I know there will be variation in the fiber; for example, the time of year it is harvested. There are guidelines and formulas for what usually works, but each fiber asks for something different and might respond differently to cooking, beating or sheet formation. You make your best attempts to use formulas or strategies you have tried before, but it’s always a test; it’s always a new experience. This way of trying out new ways of doing things, changing variables, exploring pattern and variation based on previous experience is both exciting and unpredictable at the same time – what if it doesn’t work? It’s a layered process. There are many steps before any finished product is in sight. A choice or change in any one variable can produce dramatically different results. Artistically, this repeats itself in varying iterations and cycles. Moving towards final work is a process of looking close and far – working, stepping back, working, stepping back. And, hopefully, all along, listening to what the material is asking or saying.

In an interview in the 1978 film Of Forms and Growth, Ruth Asawa speaks of how her experience at Black Mountain College, an experiment in artistic and inter-disciplinary education, influenced her approach:

When [Josef Albers] gave a class, say in paper, you weren’t talking about going from paper, which is not very important, and next you go into glass and then next you go into wood and then finally you graduate to plastics because that’s sort of the modern material. But, we always went from paper to paper to paper to paper. To make paper do what it hasn’t done yet, so you’re only talking about paper. And then when you’re through with the lesson, then you fold it and put it back in your drawer. It’s paper again… What he was talking about was abstracting from the material rather than being concerned about your own design ideas and forcing something into it, what you do is you become background. Just like the parent allows the child to express himself, and the parent becomes sort of supportive… What Albers did graphically, Bucky [Buckminster Fuller] did by trial and error, just by putting marbles and pieces of paper together. Then he proceeded to unload his tiny little aluminum trailer, all these things kept bouncing out. And, then his idea to the college when he said, ‘well, I’m the most successful failure.’ What I feel close to him about is that he gathered all of this information out of his own experience. For me, Bucky talks about basic principles. The use of the material to create a shape that can only be done by that material – that combination is what I’m interested in. The thing that really impressed me most about both Bucky and Albers is that they made a lifetime commitment, they weren’t interested in ideas that were solved, they were only interested in ideas that didn’t have a shape yet.

Asawa’s process is a glorious rhythm of working on inside and outside surfaces simultaneously, intuitive and graceful. She describes a piece by saying, “This one here, where the center one is in here and it then comes out and surfaces and goes in again and goes out again and comes around, so that this is a continuous surface. The thing that influences me are the proportions that I see when I am working on a thing, I am conscious of this kind of shape out here. And, that shape by itself is not very interesting, but when I put one next to it, then I look at this shape that is out here.” In and out, back and forth, observing shapes and forms in relation to one another.

Source: http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/09/21/ruth-asawa-tending-the-metal-garden/

The ideology of change and value in experimentation has larger social implications: Dwight and Bev’s prairie restoration could affect the land in ways that reverse the ecological effects of industrial farming, considering alternative fibers and recycling efforts in papermaking begins a critique of modern industrial papermaking worldwide, just as efforts in changing pedagogy in schools (as Black Mountain college did) might produce generations of students who think differently about the world and their role in it. On a smaller, individual level, change could look like experimenting with shifts in day-to-day choices and practices, whilst embracing the idea that patterns can transform. Knowing that change takes time, just like it takes 4 years to understand how to best harvest a new seed. And, that’s what might make experimentation pretty radical: new, deep discovery, the understandings of honoring an intention, cultivating projects and practice, developing observations and craft.

References:

Art as Experience: John Dewey on Why the Rhythmic Highs and Lows of Life Are Essential to Its Creative Completeness

https://www.brainpickings.org/2016/02/11/art-as-experience-john-dewey/

Black Mountain College

http://www.blackmountaincollege.org/history/

Dewey, John. Art As Experience. New York: Capricorn Books, 1934.

The Prairie Flower

http://theprairieflower.com/About%20Us.htm

Excerpt from Ruth Asawa: Of Forms and Growth, Robert Synder, c. 1978, Masters & Masterworks Productions, Inc.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T5eyKMEQizY