Claiming Space, Creating Space

by Jenie Gao

How do you quantify the value of a place, and determine the amount of space it deserves to claim? How do you measure the worth of a life, and the home and wellbeing that this life is worthy of?

These are questions that I have found myself regularly wrestling with in different contexts. As an artist, I have always been drawn towards working big. I like work that occupies enough space to confront and immerse people. I believe in the power of art to transform the spaces people share, both physical and mental. My love of large-scale work translates to a metaphorical question of what it means to claim space.

When I used to work in corporate, claiming space meant taking a seat at the table, and seeing that those who took up the most physical space often also had the most speaking time. In the last few years, I have had the privilege (and sometimes pain) of pursuing my career as a full-time artist. Now in my art practice, claiming space has both conceptual and commercial implications. Conceptually, it’s about expanding the boundaries of your ideas through your work. Commercially, it’s about who has access to what resources, and the authority and autonomy to decide how to use them.

To occupy space meaningfully, you also need to learn how to create and cultivate. Ideas need space to grow. Research, like seeds, needs time to germinate. Every creative process requires time to collect in order to connect. Part of my purpose here at Iowa Lakeside Laboratory is to collect information and see what grows from it. In my first week, I have spent a good amount of time listening to and observing the prairies, wetlands, and the life forms that inhabit them. Here’s what they have taught me so far.

From the Prairies

Much of what we see depends on what we cannot see. On my first day at Lakeside, I joined the Ecology students to visit a prairie nursery called The Prairie Flower. The owners of the nursery have restored their land with native plants. They harvest and sell the seeds for prairie and wetland restoration around the country.

It was the day after a rainstorm and the earth was saturated. Out in the field, we did a test that everyone should see. We placed a tin cylinder on top of the soil and filled it to the brim with water. The soil absorbed all of the water in 40 seconds. By contrast, on our way home from the field trip, we stopped at a cornfield and performed the same test. The water sat in the can for 5 minutes and none of it drained into the earth. What does this mean?

Jenie Gao – Artist Update – Week 1 Update 01 from Lakeside Lab AIR on Vimeo.

Below the surface, the prairie plants work wonders. Some of their roots go 20 feet deep, carrying rainwater with them. When the roots die, they leave behind open channels that also hold water. The porous soil has no trouble absorbing 30 inches of rainfall. The roots also hold the soil together, prevent erosion and flooding, and keep sediment from muddying up the streams. Farm plants—combined with farming practices—do none of these things. They strip the soil of nutrients and pack it down tight. When the soil can no longer hold water, the rains sweep the topsoil away, and with them, any waste products and chemicals into the streams.

When we look at things from the surface, it can be hard to imagine that the world wasn’t always this way. The North American Midwest used to be dominated by tallgrass prairie. 85% of Iowa used to be tallgrass prairie. Today, 0.1% remains. If we think the loss of landscape above the surface is immense, we can only wonder what this means for the loss beneath our feet.

From the Wetlands

I continued my studies of the habitat by joining the Aquatic Ecology students on another escapade. We visited a small marsh called a fen, where groundwater surged up and rainwater collected to create a secluded haven in the middle of a grove of trees. The earth was spongy and jiggled like pudding under our boots. Running alongside the fen was a stream.

Everything that collects in little marshlands like this fen eventually flows to larger bodies of water. This fen drains into the streams that feed Milford Creek, which flows into the Sioux River, then the Missouri River, and finally the Mississippi River, which ends at the Gulf of Mexico. The middle 40% of the United States is the watershed that drains into the Mississippi River. While we cannot see it from the Midwest, there are currently 6,000 miles of Oceanic Dead Zone in the Gulf of Mexico. It’s evidence that who we are locally becomes who we are globally.

From the Smallest of Life Forms

I’ll be the first to admit that I can be an insufferably precise person. I keep spreadsheets and collect data on the books I read and on how I use my work time. I alphabetize my spices and label my kitchen cabinets.

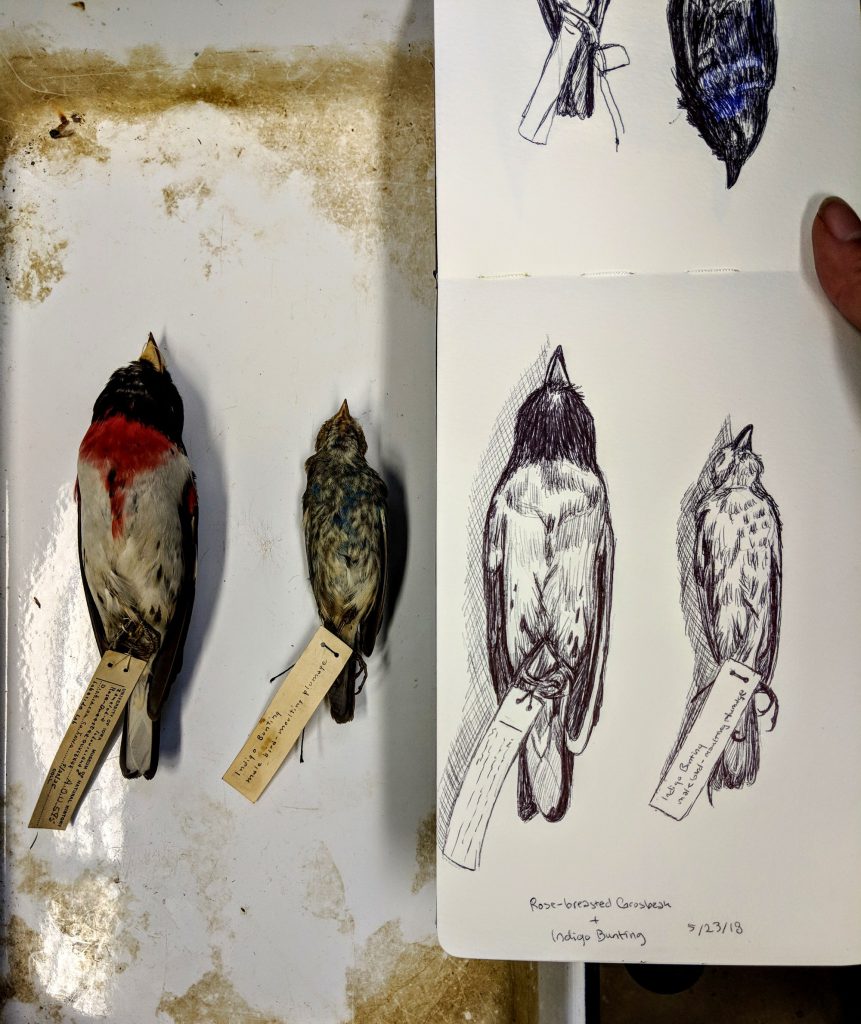

There is a game I like to play, where I “discover” new units of measurements. Here’s a fun one. The average Black-Capped Chickadee weighs between .33 and .5 ounces. There are approximately 19 million chickadees in the United States, whose cumulative weight is 7.6 million ounces, or 475,000 pounds. If the average American human weighs 180 pounds, this means that the entire population of Black-Capped Chickadees in the United States equals the weight of 2,639 people. This is slightly less than the population of Milford, Iowa, where Iowa Lakeside Laboratory is based. It would take 12.5 Chickadees to equal the height of a 5’6” person. In other words, if you stacked all the Black-Capped Chickadees in the United States, they would equal the height of 1.5 million people, or roughly half the population of Iowa.

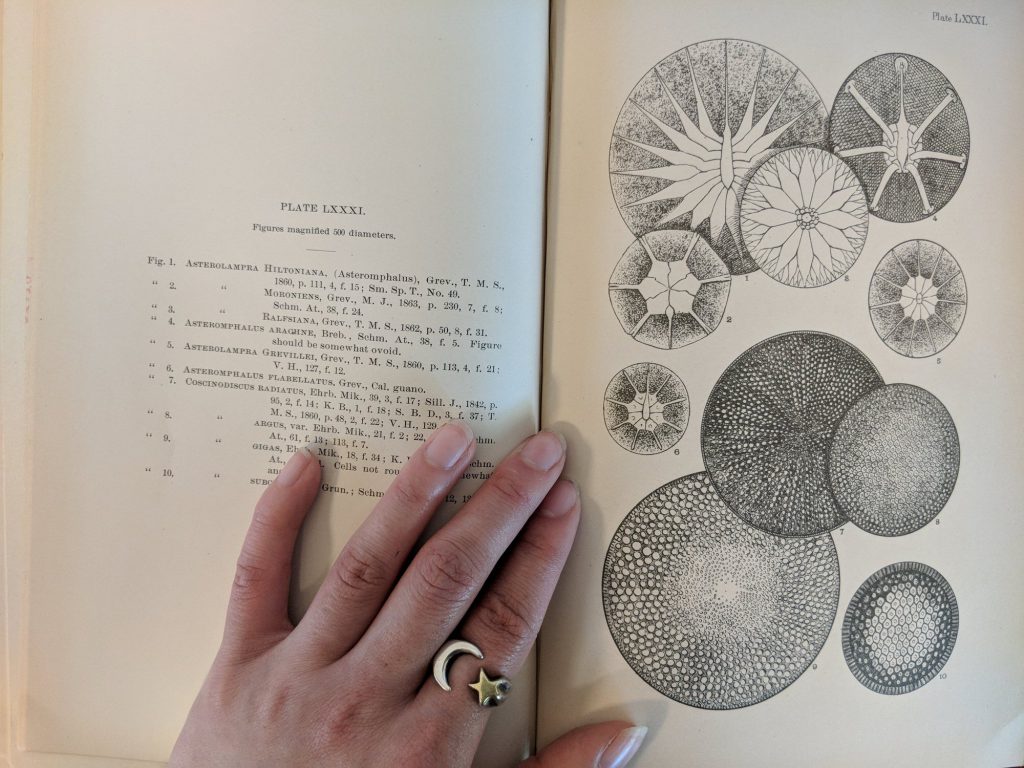

Let’s go a unit smaller, to a microorganism known as a Diatom. Diatoms are single-celled alga with cell walls made of glass. They measure between 2 and 200 micrometers. You could also say that the average Chickadee is between 750 and 75,000 diatoms long from beak to tail.

Diatoms number in the trillions, and perhaps even more impressively, create 25% of the oxygen on the planet. As a primary food source for worms and other small organisms, they form the base of the food chain for all species. Individually, they take up almost no space. Yet collectively, beyond claiming space, they create habitat for all other life forms. Scientists, including the students here at Lakeside, study diatoms as indicators of how the environment has changed. If you study soil 10 centimeters below the surface, you have a historic record of 100 years. The communities of diatoms that have lived during that time tell a story beyond their own.

In his book, The Body Keeps the Score, researcher Bessel Van der Kolk discusses the ways in which people’s bodies remember and record the effects of past traumas. The land, like the body, keeps score, and the communities of diatoms changed drastically in the last 200 years in response to European settlement. There is something poetic and delicate about gazing inside the glass bodies of diatoms to “listen to” the earth and learn what happened when people broke the land.

Further Thoughts on Space and Habitat

Iowa Lakeside Laboratory stretches across 147 acres beside West Okoboji Lake. The people here are working hard to restore the native prairies and wetlands. The site brings students and researchers every year to study and expand the realm of environmental science. Artists-in-residence like myself come to study alongside the ecologists, to expand our knowledge base, and to communicate what we have learned.

Outside of this ecological bubble, the surrounding lakes draw hundreds of thousands of people for the summer tourism. This kind of activity is the name of the game for many small towns and any larger city looking to attract new economic activity. Commerce is the game, development is the strategy, and territory is the prize. Yet if we look at the origins of the word, commerce, com + merx, we find that it literally translates to “coming together for the exchange of goods,” and that merx is also the root of mercy. By definition, compassion is built into the game.

A few miles away from Iowa Lakeside Laboratory, there is a Purple Martin colony, living in human-made bird housing. As I learn about these efforts to restore wild habitats, I find myself wondering, how does our philosophy towards the land impact philosophies towards managing civilization? Do we design with the belief that habitat loss is inevitable, and therefore housing decidedly scarce? Is the value of the land based on what it can produce, or on its rarity once it can no longer produce?

Is it possible to reframe how society at large sees and values space? Beyond utility, entertainment, commercial value, or even sentiment, a space is more than the roles it fulfills for people. If we can see ourselves as stewards of our environment, perhaps we can also see that the environment is a steward of those who inhabit it, including us.

Jenie Gao – Week 1 Update 02 from Lakeside Lab AIR on Vimeo.

The prairies once occupied 2.4 million acres of North America. Less than 1% remains. There are efforts now to reseed 8,000 more acres with native plants, not quite half of one percent of the territory the prairie used to occupy. But it’s a move in a hopeful direction, and proof that we can envision space—and who lays claim to space—differently.