Small Living / Living Small

by Jenna Bonistalli

Paying attention is a form of reciprocity with the living world, receiving the gifts with open eyes and open heart. – Robin Wall Kimmerer

I had a chance to go on a canoe ride with Mindy Morales-Williams’ Aquatic Ecology class on Tuesday. It was their second day of class, and they were collecting samples from various areas of the lake (shoreline, deep water, wetland, etc.) to observe and study under the microscope. As we paddled along the shore, getting closer to Mama Eagle’s nest, bubbles started vigorously percolating up beneath the boat. Mindy explained it was methane releasing underneath the layers of soil and suggested we collect a sample from that area. Carefully aligning our canoe with her kayak, we held each other’s boats, while she scooped a sample of mud from the lake bottom. Into a tupperware it went, and we continued paddling.

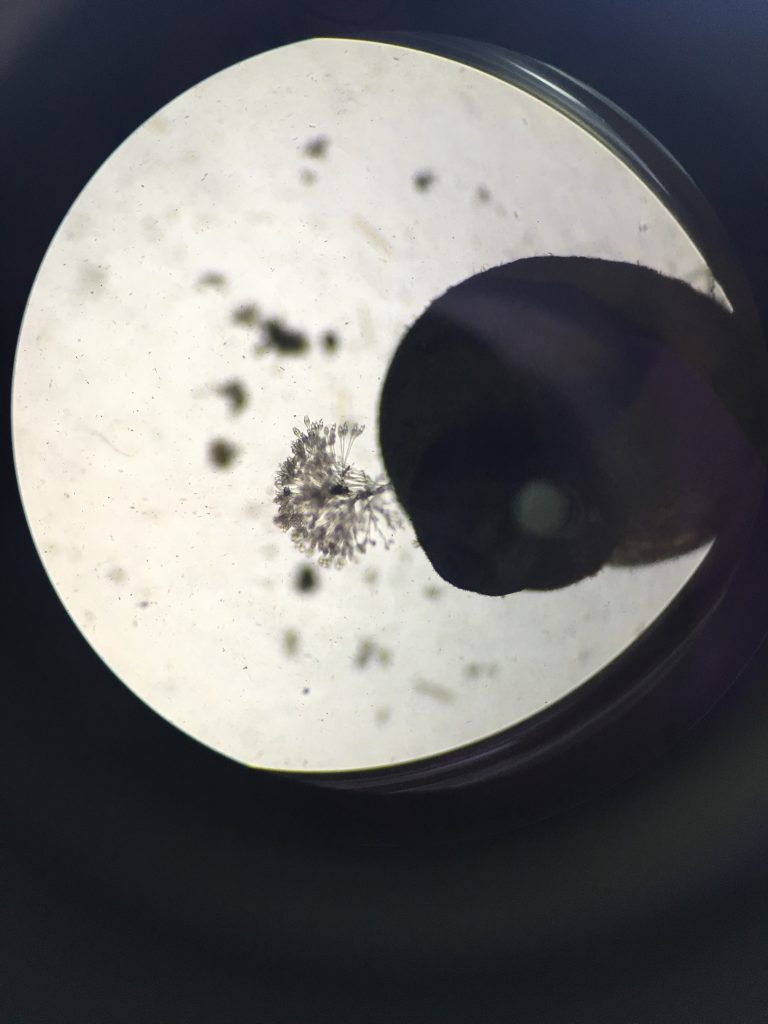

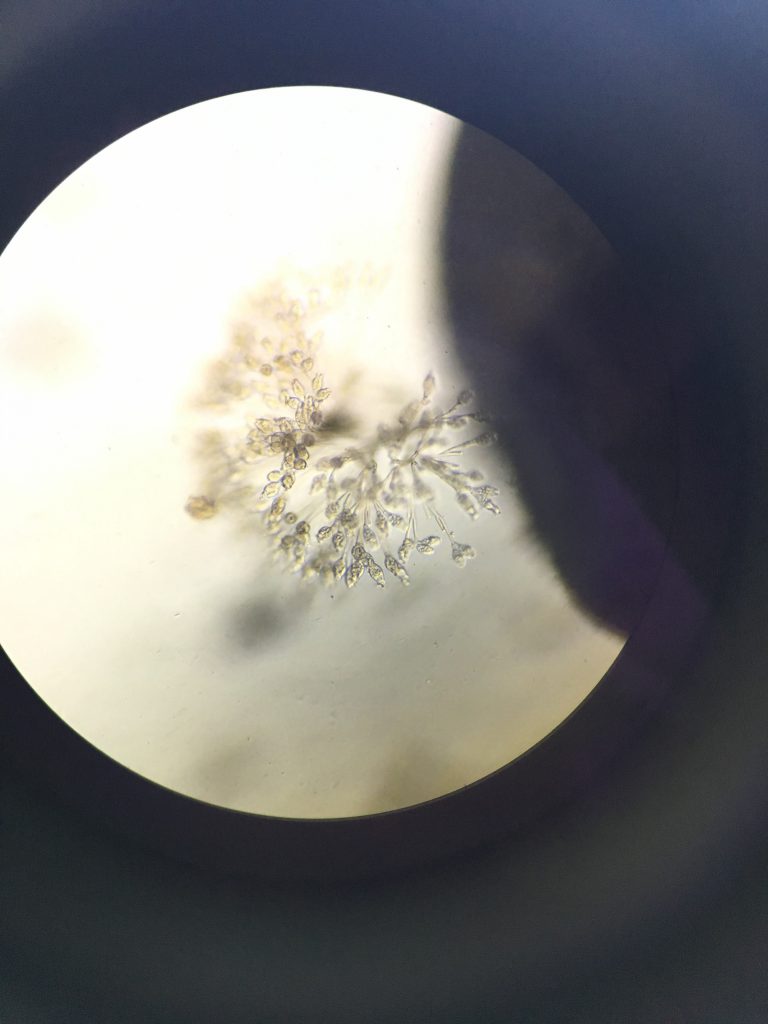

Once we got back to the lab, we took these samples to the microscope. After looking at water samples from the different areas, a dazzling array of diatoms and a few very small shrimp-like swimmy creatures, I noticed this tiny, tiny snail shell, only about 2 mm in size. We tweezed it onto a slide with a bit of its own water and arranged the microscope to its highest setting.

Under the bright light, the shell became a dark shadow. Attached to it by a tiny little thread was a beautiful, elegant floret-like shape, dancing under the microscope. It was moving, slowly, in and out, almost breathing or feeding. With the same awe of seeing something beautiful one never knew existed, I fell in love with this little organism!

We called Mindy over to see, and she told us, “This is a grouping of vorticella!” She noted this was a particularly well-endowed (and beautiful) cluster. After some research, I learned vorticella is a genus of bell-shaped protozoan ciliates that have stalks to attach themselves to substrates. The stalks have contractile myonemes, allowing them to pull their cell body against the substrate. They are named vorticella because their cilia create vortices, whirlpools. They look like a little bunch of seaweed. There are over 200 species of vorticella, and they are mainly found in freshwater environments: mud, moist soil, plant roots. They feed on bacteria and oftentimes their presence inhibits the growth, development and emergence of mosquito larvae. They have even been explored as a method of biocontrol for mosquitoes.

I immediately wanted to return every bit of that mud to the lake, so these tiny organisms could continue their life, their work: their ecological purpose. I can’t describe it exactly — I felt a very specific, discrete connection with and responsibility to this little critter. I had a million questions: What do they do? Where do they live? What is their role in the ecosystem of the lake?

Over the past few weeks, I have been reading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Kimmerer is a botanist, who writes about her relationship to the natural world through both her lens of scientific study as well as that of her cultural heritage, Potawatomi Native American Indian. As I continued reading this first week at Lakeside, the resonance and relevance in her text was profound.

Over and over in her work, Kimmerer repeats the precept, “all flourishing is mutual.” She begins with an example of studies of mast fruiting in Pecan trees, describing how the trees in the forest are “often interconnected by subterranean networks of mycorrhizae, fungal strands that inhabit tree roots. The mycorrhizal symbiosis enables the fungi to forage for mineral nutrients in the soil and deliver them to the tree in exchange for carbohydrates.” The mycorrhizae often form fungal bridges, connecting all the trees in a forest. These networks balance and redistribute the carbohydrates from tree to tree. She describes a “web of reciprocity” they weave, giving and taking, acting as one, connected by the fungi. Through unity, the forest flourishes: “Soil, fungus, tree, squirrel, boy – all are the beneficiaries of reciprocity”(20).

Like the mycorrhizal network, this tiny world of the vorticella is generously working wonders for freshwater ecosystems. And, I believe it is our work as artists and scientists to honor these small living worlds, as well as offer moments of connectivity for other humans and the sake of our earth. To begin to approach the question: how shall we live here?

Speaking of vortices, in much of my creative work and life this past year, I have been paying closer attention to forms and patterns of human consumption. When I say consumption, I mean its broadest definition – attention, material, spiritual. I wonder how certain patterns and practices of human beings influence our connection to and communication with other members of the natural world (cellular, animal, plant). Of pecans, wild strawberries and leeks, Kimmerer writes, “how generously they shower us with food, literally giving themselves so that we can live”(20). What is our response? Our reciprocity?

Kimmerer describes the indigenous canon of principles and practices that govern the exchange of life for life: the Honorable Harvest. She writes that the details of the Honorable Harvest are highly specific to different cultures and ecosystems, but the fundamental principles shape a relationship with the natural world and rein in a tendency to consume, so that the world might be as rich for the seventh generation as it is for our own. She writes, “The guidelines for the Honorable Harvest are not written down, or even consistently spoken of as a whole – they are reinforced in small acts of daily life. But if you were to list them, they might look something like this:

Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them.

Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life.

Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer.

Never take the first. Never take the last.

Take only what you need.

Take only that which is given.

Never take more than half. Leave some for others.

Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.

Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken.

Share.

Give thanks for what you have been given.

Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken.

Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.” (183)

Like the leeks and the marten, the ideas of Honorable Harvest are an endangered species. Kimmerer writes that they arose in “another landscape, another time, from a legacy of traditional knowledge. That ethic of reciprocity was cleared away along with the forests, the beauty of justice traded away for more stuff…. Wild leeks and wild ideas are in jeopardy. We have to transplant them both and nurture their return to the lands of their birth”(201). From what I have seen at Lakeside Lab this week, this reverence and return to the land is so much the work of scientists. People here are paying attention all the time, building on years of observation, knowledge, experience, curiosity and maybe most importantly: wonder. Every moment is an opportunity to notice something. And, as Kimmerer describes, this close attention is a form of reciprocity to the living world. From taking water samples with high school students, to surveying fish populations through conversation, to restoring prairies to grace the edge of the lake, oftentimes the work of scientists seems a modern day homage to doing better for and with our world. Of this connection, Kimmerer writes:

Because we can’t speak the same language, our work as scientists is to piece the story together as best we can. We can’t ask the salmon directly what they need, so we ask them with experiments and listen carefully to their answers. We stay up half the night at the microscope looking at the annual rings in fish ear bones in order to know how the fish react to water temperature. So we can fix it. We run experiments on the effects of salinity on the growth of invasive grasses. So we can fix it. We measure and record and analyze in ways that might seem lifeless but to us are the conduits to understanding the inscrutable lives of species not our own. Doing science with awe and humility is a powerful act of reciprocity with the more-than-human world. I’ve never met an ecologist who came to the field for the love of data or for the wonder of a p-value. These are just ways we have of crossing the species boundary, of slipping off our human skin and wearing fins or feathers or foliage, trying to know others as fully as we can. Science can be a way of forming intimacy and respect with other species that is rivaled only by the observations of traditional knowledge holders. It can be a path to kinship. (252)

The essence of a gift economy is relationships, where the primary currency becomes honor and reciprocity. “A gift comes to you through no action of your own, free, having moved toward you without your beckoning. It is not a reward; you cannot earn it, or call it to you, or even deserve it. And yet it appears. Your only role is to be open-eyed and present. Gifts exist in a realm of humility and mystery – as with random acts of kindness, we do not know their source …“(Kimmerer 24). I reference “living small” as much as I might say “living reverently:” with presence, seeing the world – and its every tiny part – as a gift. I didn’t know I was going to meet these little vorticella on a casual Tuesday, but I’m so happy we made each other’s acquaintance.

References:

Kimmerer, Robin W. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013.