Imperfectly Perfect: Toward a Middle Way of Nature’s Chaos & Order

by Brian Schorn

For the last three weeks, daily, close observation and contact within the natural world has led to two experiential realizations: 1) everything is changing (impermanence) and 2) the seemingly perfect design of all things is refreshingly imperfect. These realizations have been helpful in both my personal and professional lives.

In twenty-one days, I have seen the prairie transform, replacing old growth with new. Grasses that were once one foot tall when I arrived are now five feet tall, gracefully swaying in the wind. During my first few days here, I collected a lot of old plant growth for art material. After starting a number of new projects, I needed more materials. So, during the third week, I went back into the field only to realize that the new growth was taking over and the old was now difficult to find. I began to see this in week two with last year’s, fallen-over goldenrod galls. The realization became very clear to me: everything is in a constant state of flux. A plant that was once there a week ago, is no longer visible as it decays into the soil; and, new plants are growing wildly in their place. Taking the time to see everything in nature change, allows for the notion of impermanence to really settle in. If everything is changing, then nothing is permanent. I was caught up in this trap by thinking that, just because I collected dried plants in a certain location two weeks ago, the same ones would be there two weeks later. They are gone and something else is there now.

Working closely with these natural materials in my art, I marveled at their design—their diversity, elegance, intelligence, but most importantly, their sacred geometry. This geometry is sacred because it is a design strategy that seems to apply to all living things. For example, the bilateral symmetry of a single-celled, pennate diatom compared to the bilateral symmetry of a human being. It is powerful, and it appears to be perfect. This perfection is something that I’ve been hooked into thinking is the way things should be. I find myself saying, “Well, it seems to be this way in nature, so why can’t I do it too.” Perfectly straight lines, perfect circles and everything lined up and situated just right. Although, upon further examination of marsh plants, I found seemingly perfect, basic geometric shapes of their stems: square, triangular and round. Round, yes, but I never realized there were stems with other shapes like triangular and square. As I began to work with them and force their natural forms into rigid pre-determined grid structures, I realized that within these perfectly-designed, sacred forms was an unexpected underlying quality: imperfection (malformation, asymmetry, mistakes, flaws, irregularities, uneven lines, discoloration, etc.). In other words, everything seemed to be perfectly imperfect. How refreshing!

Week three started off with a jolt of energy generated by the curiosity and fascination of about 25 four to five year old kids. I volunteered to help with the Saturday morning Spirit Lake library kid’s nature program. Before the kids arrived, I spent a long time with the display examples and living creatures. I was so excited to see a planarian slithering about in a pan, while recalling my first time seeing one as a youth. The saying, “Once a kid, always a kid” was precisely the case here. My curiosity and sheer amazement of all things natural was running wild.

The naturalists did an amazing job of presenting complex information about animal homes in a fun and engaging manner. We all learned about bee’s nests, goldenrod gall flies, turtles, snails, caddis flies, robin, heron and marsh wren nests. After a presentation and some songs about animal homes, the kids gathered around work tables with lots of different materials and tools to play with. They each created their own version of an animal home based on what they just learned. The other artist-in-residence and I each helped stimulate the creativity of the kids to get them started. The results were amazing. In particular, two boys made bee’s nests that were created out of torn paper and twigs including an entrance hole for the bees. Another created a snail shell and its surrounding environment out of a plastic cup and construction paper.

Over the weekend, I worked on my week two report. On Friday evening, I joined some of the faculty at Okoboji Brewery and tried a Firestone Walker Nitro Merlin Milk Stout. It was really good and a wonderful evening to sit outside and socialize with the artists and scientists. On Saturday, all of the artists-in-residence were invited to dinner at another faculty member’s home. We had some freshly caught fish and excellent rhubarb pie. After dinner, we watched a pregnant, whitetail deer lay down in the grass about 50 feet from from where we ate. We then went for a walk around Lake Okoboji, stopping to catch some Daphnia in the water. There were thousands of them swimming around in the tiny jar. So much vibrant life is happening all around us, but we tend to not be aware of it, especially at the microscopic level. This was a reminder of that.

On Sunday I started a new piece called “Alternating Sedges.” Sedges have edges and an unusual triangular stem. I collected a batch during my first week and decided to make something with them, so I cleaned off all of the dried leafy material leaving only the stem. I struggled at first and seemed to be fighting the natural order of things, until I realized that if I cut just above each node, I could simply pull off all the the leaves in a single stroke, like a sleeve. Once the sedges were all cleaned, I cut them into two inch pieces. Then, I prepared a white board as a back support and used graphite to draw in a two inch grid. Based on the idea of alternating the direction of material in previous work, I decided to use the same approach. This was a great example of discovering how the seemingly perfect triangle and straight lines of the stem were, in fact, not perfect or straight. This was not easy to accept, but slowly I let go of this concept and allowed the stems to be as they are: perfectly imperfect.

Early on Sunday afternoon, I determined that I would not have enough sedge stems to completely fill the prepared back support grid, so I went out to Three Conners (3 corner marshes at a gravel road T-intersection) with a botanist to collect more. The botanist found a patch of them and directed me to the area saying, “I’m going to measure some water temperatures up the road. I’ll be back in a little while.” So, I found the patch of sedges and, with my knee-high rubber boots, waded into the marsh. I collected a full pail of sedges and decided that I had enough to complete my new piece. Getting out of the marsh, standing on the road, I looked around 360 degrees at the waving grasses and listened to the red-wing blackbird calls. I was the only human around for as far as I could see. It was a frightening, eerie feeling. I quickly realized that I was a part of the ecosystem, just like every other organism out there. Thoughts begin to instinctually form, like “Where can I find shelter?, Where can I find food?, Who are my predators?” As a breeze shifted the direction of the grass to the gravel road, I could see the dusty trail of the botanist’s car as he approached. The thoughts subsided.

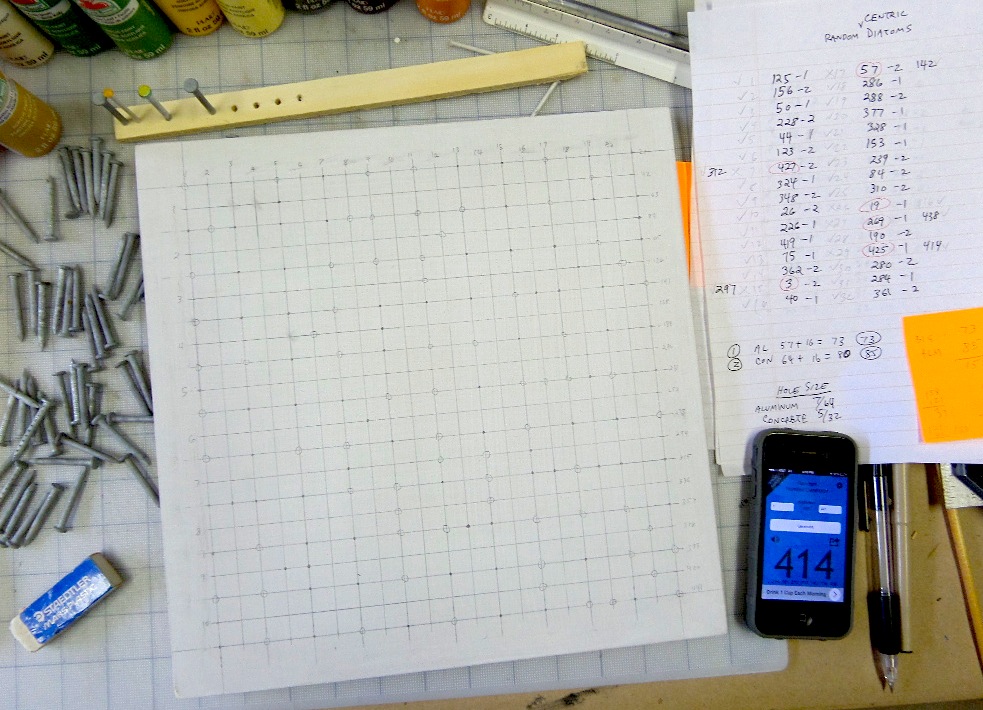

During the beginning of the week, I worked on two pieces: “Centric Diatom Collection” and “Alternating Sedges.” For “Alternating Sedges,” I began gluing the two inch sedge pieces into the grid system. This was tedious and challenging, with a lot of glueing yet to do. I brought a prepared 18”x24” white board for collaging hundreds of confetti pieces. This idea slowly transformed into something more specific after last week’s diatom study. Instead of using the 18”x24” board, I prepared a new, smaller board that was thick enough to drill holes into and support long nails. This would become “Centric Diatom Collection.” After drawing a grid of 441 intersecting points, I devised a method to determine the locations of two different types of nails that totaled 153. With all of the rigid order and perfection I was encountering, I decided to add some irregularity, so I downloaded a random number generator to my phone. Using this app, I randomly determined the location points and which of the two nail types were used. Then, 153 holes were drilled using two different sized bits. Nail preparation consisted of painting half of the nails white (the other half was already white) and the heads of all of them a variety of dark colors. Once the paint was dry, I glued tiny, confetti dots of colored paper onto the heads of each nail. Nearly all of the choices regarding size and quantity of the new works are being determined by what materials I have at hand. In other words, working with things as they are.

Later in the week, I started two new works, gessoing and painting the back board supports. The two new pieces include, “Earth Enso” and “Goatsbeard: A Scrambled Sideview.” Using a found piece of circular plywood about two feet in diameter, I glued soil to the surface and edges, then primed and painted it white. This will serve as the background for an enso form, a Japanese, calligraphic brush stroke representing present-moment awareness and the cyclic nature of all things. The enso form is a syrofoam ring two inches thick and about 16 inches in diameter. It has been painted black. Next week, I will glue black soil to the foam ring and attach it to the white support board, creating a contrast of black and white, while each piece shares the commonality of a soil-encrusted texture.

The second piece originated from finding some used, rusted hardware that appears to hold something perpendicular to the wall. So, I prepared a support board to attach the hardware. A second, smaller board was cut to fit perpendicular into the hardware and the edges will be painted white to match the color of the support board. In effect, if one looks directly at the piece from the front, it is essentially all white. And, if one shifts slightly to the left or right, a side view becomes visible. I found an image of a plant in an old nature book that was mysteriously familiar. Not knowing the name of the plant, I consulted with Lakeside Lab’s botanist. We determined that it was a close-up of the fruiting stage of Goatsbeard, a large dandelion-type plant with an umbrella form for dispersing the seeds in the wind. Coincidentally, the next day, while walking along the trail, I saw something that looked like it, so I moved in close, and, it was Goatsbeard in an early fruiting stage with a few umbrella forms visible. The image will be be cut into one inch squares, rearranged and collaged on both sides of the perpendicular board, hence the title “Goatsbeard: A Scrambled Side View.”

The last exciting event of the week was on Thursday, when I went out with the ornithology class to band birds. We set up nearly invisible nets to trap the birds, then we would untangle them, measure and weigh them, band them and, finally, release them. The birds seemed to figure out the placement of the nets fairly quickly, avoiding them, therefore, only a robin was caught while I was there. But, I got to see the various techniques used, including the necessary steps to untangling a bird from the net without harming it, how to hold the bird once out of the net, how to measure wingspan, how to weigh, how to determine the gender of a robin and proper data collection. Interestingly, the robin we caught was banded almost one year ago to the day at Lakeside Lab by another ornithology class. Additionally, a catbird nest was found nearby, so I was able to watch while the students banded three baby catbird chicks with their pin feathers (an early form of feather growth). The day ended with a lecture on the changing whitetail deer population in the state of Iowa.

My weekly identification includes the following: Goatsbeard, Motherwort, Mink, Bald Eagle (eaglets), Bulrush, Cup Plant, Spotted Water Hemlock (poisonous, fatal if eaten), Damsel Fly, Orange Bluet, Twelve-Spotted Skimmer, Leopard Frog, Whitetail Deer, Eastern Cottontail Rabbit, 13 Lined Ground Squirrel, Caddis Fly, Spirogyro, Baltimore Oriole, Yellow Warbler, Blue Jay, House Wren, Rose-Breasted Grosbeak, American Lady Butterfly, Cardinal, Planarian and Daphnia.