Mucky Areas, Animal Behavior, and the Value of Observation

by Hannah Fisher

6/10

I began my drive to Iowa from Kalamazoo, Michigan on June 10th. It was my first trip into the state, and I really had no ideas of what Iowa or its landscape would be like. I was not altogether surprised that it was flat, but had not considered the vastness of the landscape before driving through the endless fields.

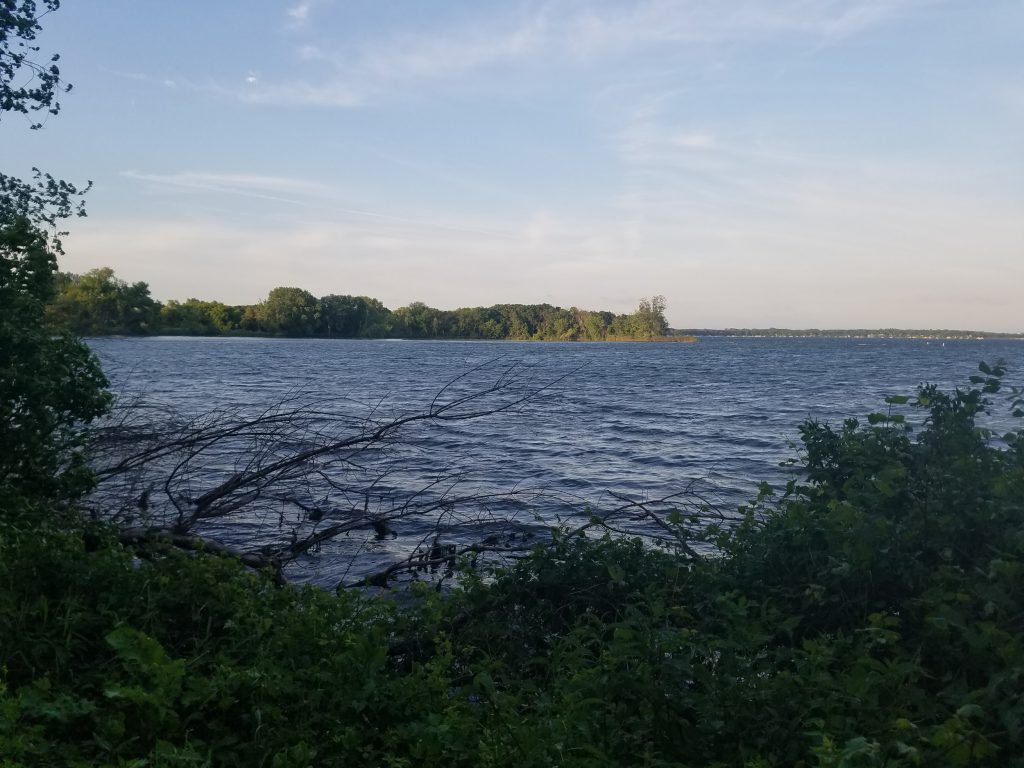

I felt vulnerable by the openness and lack of trees, but then the oasis that is the lakeside lab came into view and I immediately felt some comfort here within the trees.

I had arrived late, so I missed dinner and orientation, but Matt kindly showed me to my room and I began to show myself around the grounds – I wandered down to the lake (I was in awe of the strength of the wind off of the water), out to the Bodine Lab where our studio would be, and back to my room where I met Robert Jinkins, one of the other artists.

Robert had already been here a week and took me around to point out the important locations at the lakeside lab – laundry, closest bathrooms to the studio, kayaks, and the specimen collection in the King Lab. I met Richelle Gribble, the third artist-in-residence, on the way back to my room, and got ready to get up early the next morning.

6/11

I joined in at breakfast for my first meal at the lab, and began introducing myself around, partly in hopes that it would be a good way to hear about what was happening for classes that day. After breakfast, I continued making my way around the campus to check out the all of the buildings I had not yet seen.

I was immediately intrigued by the mucky areas down by the lake, and I thought I might try to do a study on the goings on of the water and the muck throughout the day while I wasn’t there to watch. I had brought a collection of uniform wood scraps with me, and walked around to a few spots on the lakeside to stick them down into the muck, to act as my measurement devices to collect some pseudodata on what the days looked like for the water and the muck.

I met up with Neil’s Animal Behavior class in the late afternoon as they were studying the behavior of robins hunting for worms in the strong wind. They were interested in finding if the birds had more success locating worms when tilting their heads either into or away from the wind direction.

After lunch, I joined the class as they went to the nearby canals to collect some muck to later analyze in the lab. On the trip, Neil pointed out many little details in the area around us, like how duckweed is asexual but becomes sexual in stressed conditions, and how it’s the smallest vascular plant. We took a look at how flowers adapted alongside pollinators to mutually benefit both, how bees communicate to their colonies about the location of flower patches by mathematical dancing, and the way an oriole builds its nest. I don’t believe there had been an original plan to encounter and learn about the things that we did, but as soon as we began to look around us, I realized how much there was to discover that we may have overlooked before on our original mission. Neil was an excellent guide in pointing out the little intricacies and stories in the life around us, and one of the best things that I noticed was how excited the entire group of us became by each of these little stories.

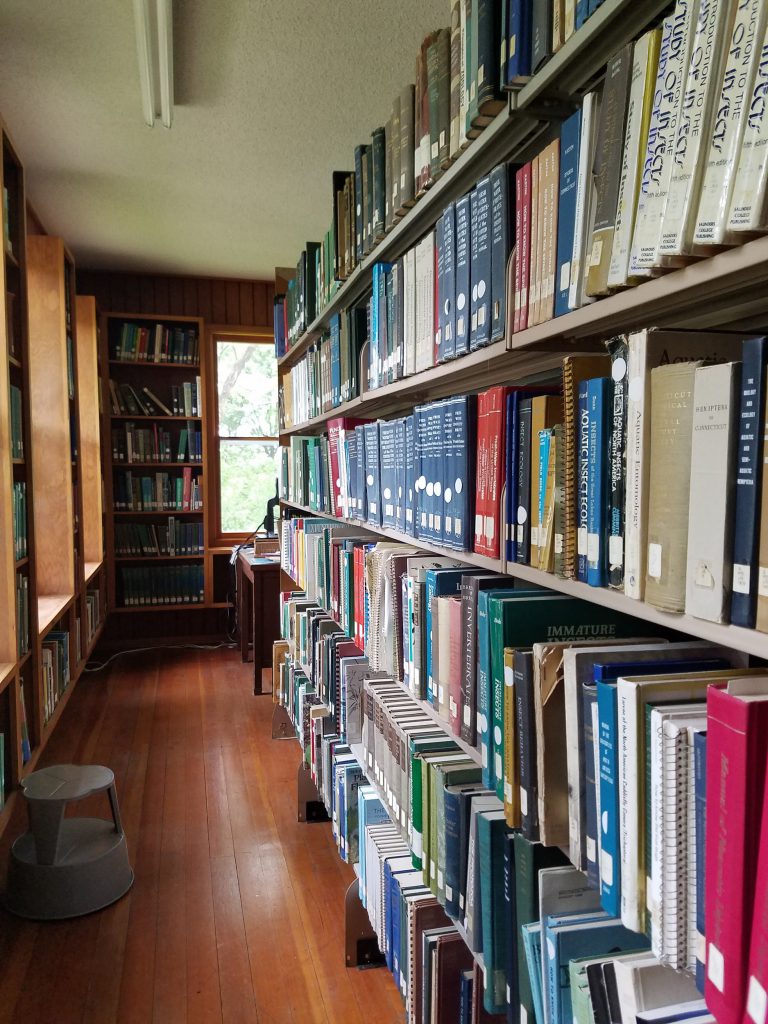

We brought the muck back to the lab and analyzed its contents by going through with tweezers and glass petri dishes – we found snails, leeches, worms, and many smaller critters that we observed under the microscope. Each time we didn’t have an answer to a question that we had about the lives of these little critters, Neil prompted us to visit the library, and to come back when we’d found our answer. The more details we learned about these little critters and the more I understood about their lives, the closer I felt to this small sample of muck and all of the lives it contained.

We did some lecturing and learned about fitness and survival, and passing on genes. It got me thinking on how generations build upon one another, and things change stemming from our ancestors’ pasts and the way we fit and interact with the living things around us. I’m also thinking about how this is all happening, driven by the complex forces inside us and outside us, and we must study and focus to understand the intent of these forces – there is a disconnect between what I experience and what my body does without my knowledge of it. And because of these underlying forces, there is a back story being told, everywhere. We just have to listen.

“The whole of nature is a telltale filter for the intelligence that has passed through it. Our bodies are part of the same filter, and from our bodies come our minds with which we read the tale” – John Berger.

After dinner, the writer-in-residence at the lab, Anna Polonyi, led a writing workshop on how field notes can be related to poetry. She explained with admiration the way that scientists like Charles Darwin were able to capture and explain observations through their notes, which was not altogether different from the way a poet captures a subject for a poem. She encouraged us to find objects around us, and describe its smell. I wrote about a rock that smelled like a Michigan basement.

6/12

I went into the Prairie Chick in the morning to get coffee, and then met up with Neil’s class on their way to a prairie nature preserve. I don’t remember the name of the location, but it was some type of wetland, and it was beautiful. It was here, with such a clear view for miles over the landscape, I began to appreciate the flatness of the prairie. I could see it all and it felt as though it was all happening at once, together with me to view it – there was such a powerful curiosity in that horizontal.

We hiked out and used the territorial behavior of a male redwing blackbird to locate his nearby nest, which contained chicks. We continued on to find leopard frogs, a garter snake, a bobolink, american white pelicans, woodchucks, and a flock of gulls. Something that really interested me was a discussion about migratory behavior of the pelicans, in which Neil mentioned the concept of philopatry – a love of home.

6/13

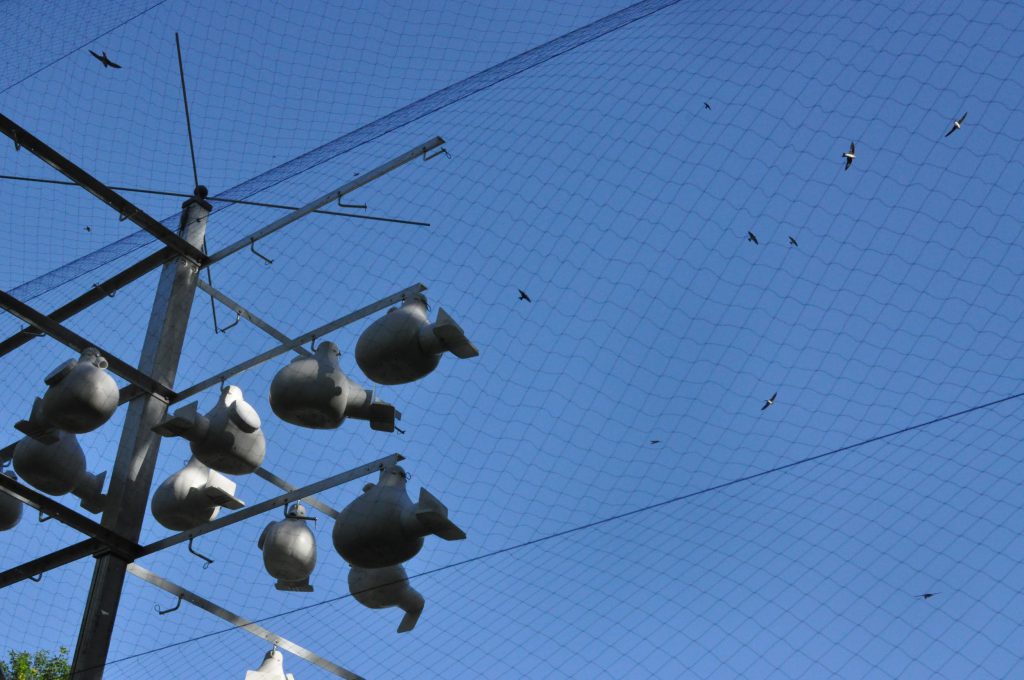

In the morning I joined in Neil’s class again so that I witness the banding of a flock of Purple Martins. We set up large mist nets and were able to catch a few females who were coming back to tend to their nests.

Wendell, the man who’s home we were visiting (he established the Purple Martin homes on his property), was talking about birds with some of the students and I overheard that no two male Rose-Breasted Grosbeaks have the exact same shaped pattern on their chests; I thought it was interesting how each bird, even of the same species, is unique and individual.

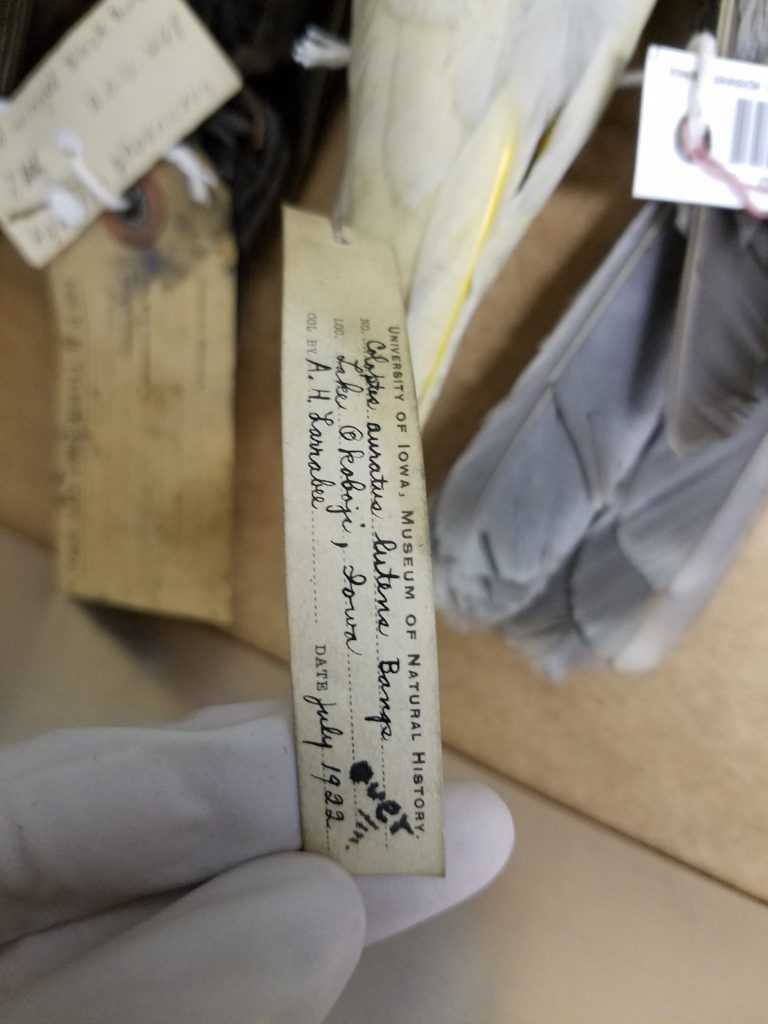

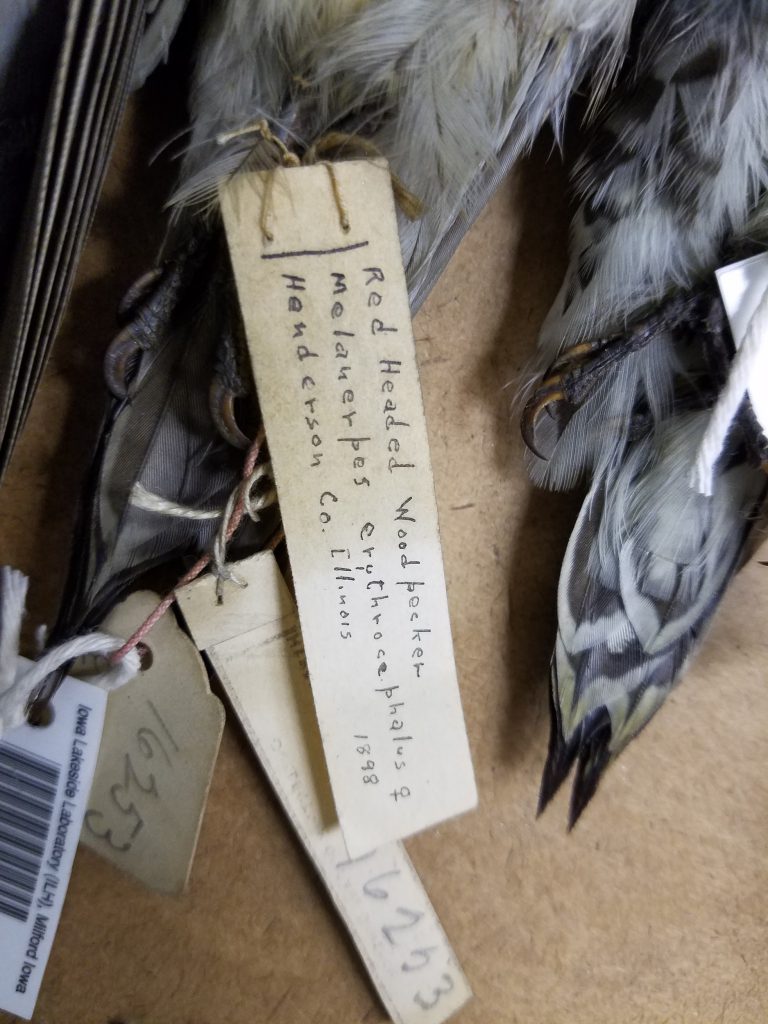

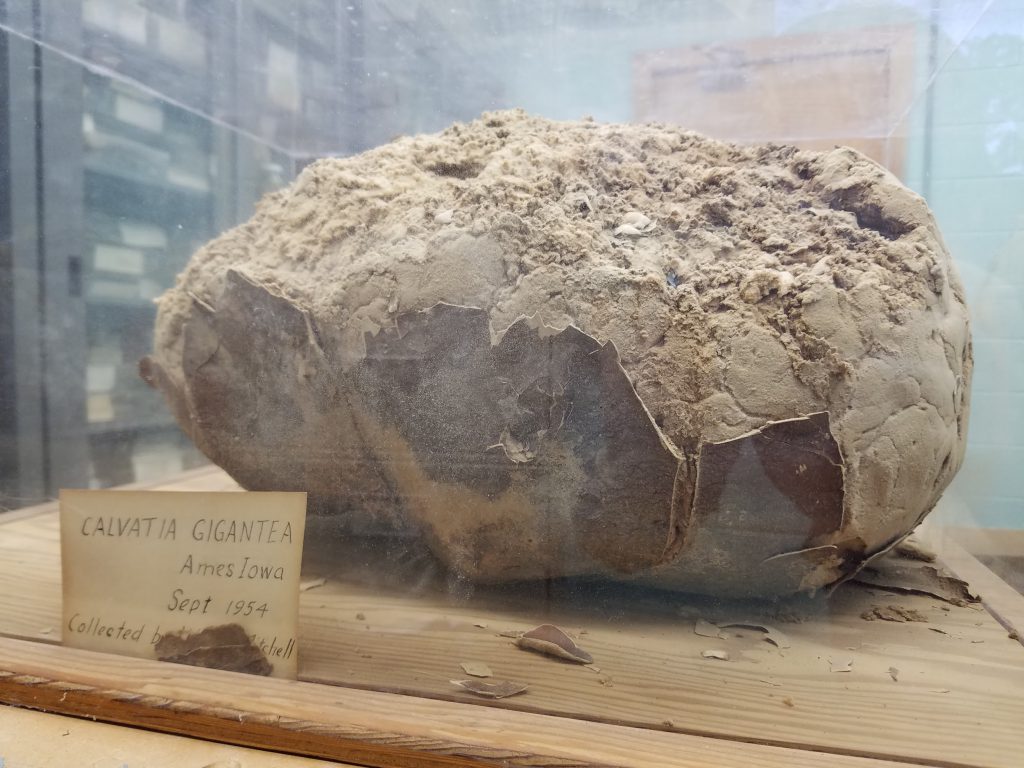

The afternoon was a rainy one, so I was able to take some time to explore the specimen collections.

After looking at the delicate ID tags on the birds, I was surprised by how old they are. I was fascinated by these identification tags that were used to describe the lives and information on the specimens, including the metal ones left in the Bodine lab for ID’ing trees and plants. I started to think about identifying things using pseudoscience, and if these specimens could be described in any other ways, to capture more than just their names, genders, and discovery dates.

In the late afternoon, Neil’s class gathered to take a field trip into town to try and find chimney swifts and nighthawks.

We walked around some buildings and while we stood on the sidewalk, we were able to locate some chimney swifts in flight – they had a unique body shape, as Neil described it, “a cigar with wings”. They were so beautiful, and strange, and bat-like, and the entire class got excited as we spotted more and more and watched them bounce around in the air.

After a while of observing chimney swifts, we determined to find the nighthawk, which Neil knew had nested on top of one of the nearby buildings. He got out his speaker and played recordings of nighthawk calls, which eventually drew out the female who had been on the nest. She soared high above the street, and the entire group of us traced each movement that she made, following with our heads and our bodies, and admired the crook in her wings as she flew.

Then, after reaching a great height, all at once the nighthawk descended, diving down toward us to swoop near Neil’s speaker, as a territorial display. As she did so, the sound of the air against her rapidly diving wings made a large “BOOM”, almost metallic-sounding. After this first display, the whole class was enamored and watched in awe as she continued climbing and diving, and we delighted with collective “Wow!’s” each time we heard that incredible sound.

For me, one of the best parts of this experience was being able to share it with a group of people who were completely captivated by acts of nature – there was an enthusiasm and curiosity in the beauty of our world, and an eagerness to watch closely and discover it together.

6/14

In the morning I went on a bike ride around Lake Okoboji; it was overcast and drizzling all morning so I decided to experiment with making a linocut print of some of the birds that had inspired me so far in Iowa. I started with an American White Pelican since their appearance in Iowa had taken me by a wonderful surprise.

Later in the evening as the sun was setting, I walked out to the eagle’s nest on campus to see if I could catch a glimpse of the adults or the juveniles which were still in the nest. As I approached, I heard a high-pitched chirping, and looked up to see one of the adult eagles perched near the nest, looking right at me. I stood observing, far down below, reassuring the eagle that I meant no harm, as it continued to chirp at me from the treetop. In that moment, it was just me and the eagle, acknowledging each other and talking, together.

6/15

In the morning, I joined in with Kalina’s class on Algae as they were exploring lake samples under microscopes. As the students magnified the samples, each specimen showed something new, some little beautiful secret.

As I hiked back to the Bodine Lab to experiment with some cotton and leaves I’d collected, I noticed a log in the pathway that was absolutely stunning – it had been naturally hollowed and had a twisted shape, with moss growing on it now. I thought about how gorgeous this little log was and wondered what it had gone through to eventually end up here, in the pathway, all twisted and hollowed and charming and just waiting to cross paths with someone.

I picked up that log and brought it back with me to the lab, because I felt it deserved some special treatment. I wanted to highlight its features and promote its individualities, each of its little secrets. I had brought with me a large piece of silver paper, so I experimented with custom-shaping this paper to fit in the chasm of the log.

6/16

It was thunderstorming again in the morning, so I worked a bit on my Pelican print. In the evening us artists and students went to a free concert in Arnold’s park across the lake, and I got to explore the amusement park and we drank fresh squeezed lemonade.